- Gender and sexual

harassment

- Ireland COSHARE North-South survey report [1]

- National Surveys of Staff and Student Experiences of Sexual Violence and Harassment in Irish HEIs [2] [3]

- Sexual harassment of women: Climate, culture, and consequences in academic sciences, engineering, and medicine [4]

- Gender-based violence and its consequences in European Academia [5]

- Violences sexuelles dans l’enseignement supérieur en France : un focus sur l’alcool et le cannabis [6]

- The Potential of Sexual Consent Interventions on College Campuses: A Literature Review on the Barriers to Establishing Affirmative Sexual Consent [7]

- Sciences : où sont les femmes ? [8]

- Pressions, silence et résistances - Étude sur les violences sexistes et sexuelles et les discriminations en milieu doctoral en France [9]

- Impact of the undressing consent program [10]

- Effects of Mandatory Sexual Misconduct Training on University Campuses [11]

- Looking for a preventive approach to sexual harassment in academia. A systematic review [12]

- Association Between Sexual Harassment Intervention Strategies and the Sexual Harassment Perception and Attitude of University Students in Beijing, China [13]

- Can I Say “No”? How Power Dynamics Hinder Consent in University Settings [14]

- Discriminations

- Understanding Research Culture: What researchers think about the culture they work in [15]

- QUELLES POLITIQUES POUR RÉPONDRE AUX DISCRIMINATIONS À L’UNIVERSITÉ ? [16]

- Gender

discrimination in academia

- The gender citation gap: Approaches, explanations, and implications [17]

- When Two Bodies Are (Not) a Problem: Gender and Relationship Status Discrimination in Academic Hiring [18]

- SHE Figures 2024 [19]

- Impact de la réforme du lycée sur l’enseignement de l’informatique : bilan et perspectives [20]

- Gendered Citations at Top Economic Journals [21]

- Recognition for Group Work: Gender Differences in Academia [22]

- Men set their own cites high: Gender and self-citation across fields and over time [23]

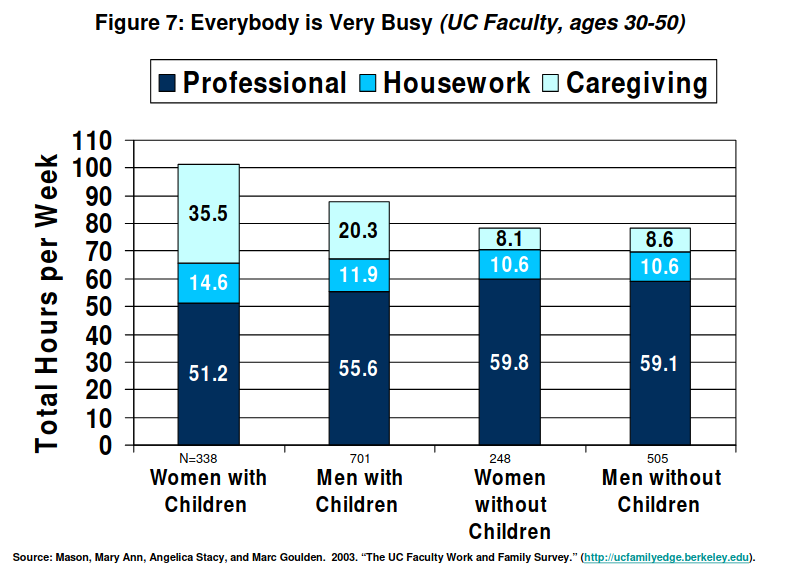

- Gender Inequality and Time Allocations Among Academic Faculty [24]

- Asked More Often: Gender Differences in Faculty Workload in Research Universities and the Work Interactions That Shape Them [25]

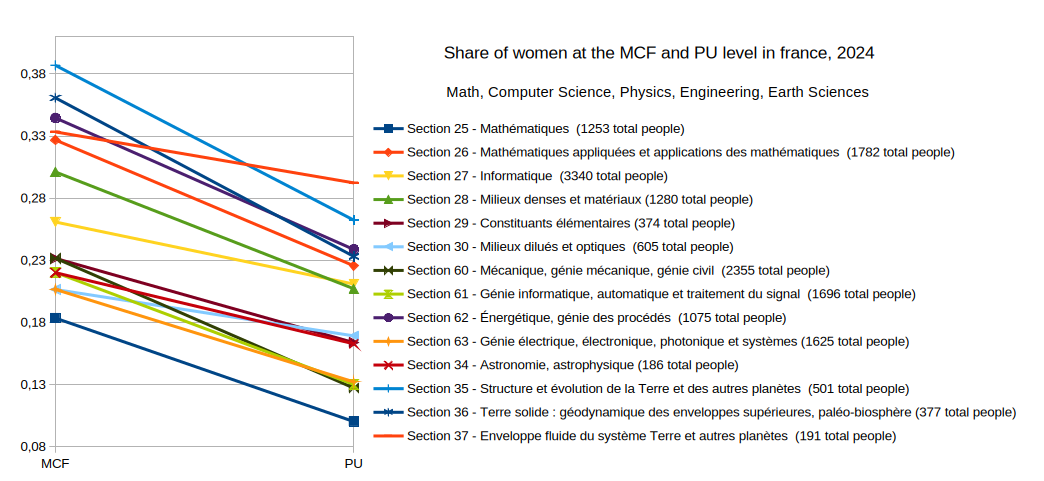

- Leaky pipeline at the full professor level in France

- Gender disparities in high-quality research revealed by Nature Index journals [26]

- Quality of evidence revealing subtle gender biases in science is in the eye of the beholder [27]

- The impact of gender on the review of the curricula vitae of job applicants and tenure candidates: A national empirical study [28]

- The Queen Bee phenomenon in Academia 15 years after: Does it still exist, and if so, why? [29]

- Navigating the leaky pipeline: Do stereotypes about parents predict career outcomes in academia? [30]

- Is there a motherhood penalty in academia? The gendered effect of children on academic publications in German sociology [31]

- Do babies matter (Part II) [32]

- Underrepresented minority (URM) discrimination

- Weight discrimination

- Statistics computations

- Toxic culture in general

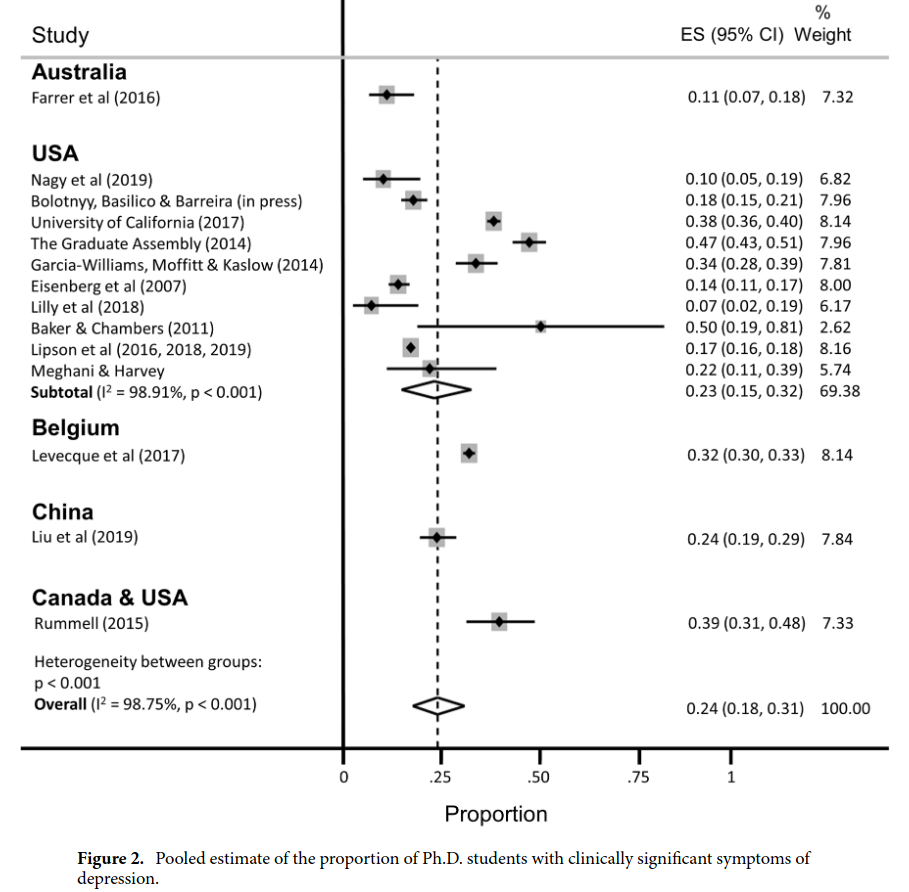

- Systematic review and meta-analysis of depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation among Ph. D. students [40]

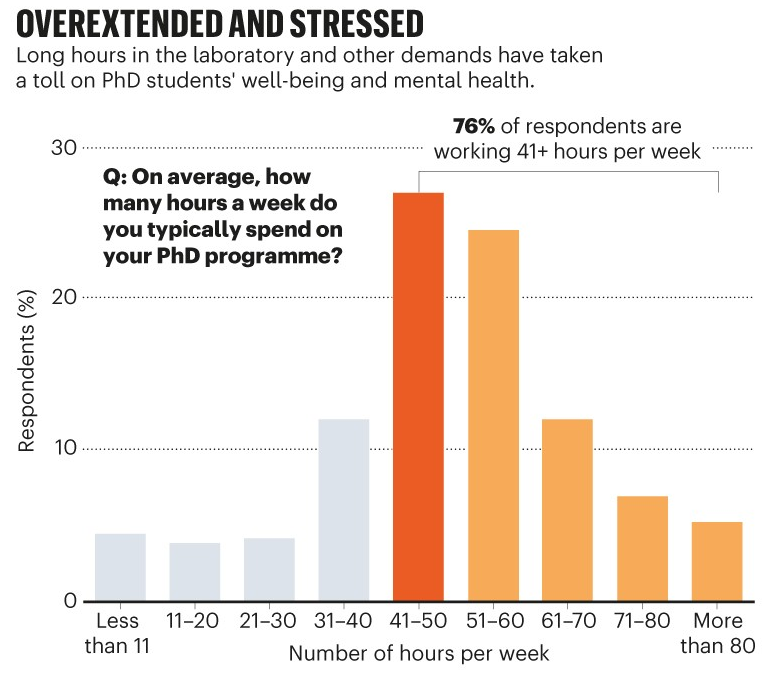

- PhDs: the tortuous truth [41]

- Joy and stress triggers: a global survey on mental health among researchers [42]

- La gestion du stress chez les doctorants : la surconsommation de certains produits qui pourraient nuire à leur santé [43]

- Looking forward

- Value of diversity

- Diversity leads to better science? Gender-Heterogeneous Working Groups Produce Higher Quality Science [44]

- Gender-diverse teams produce more novel and higher-impact [45]

- Collaborating with people like me: Ethnic coauthorship within the United States [46]

- The Diversity-Innovation Paradox in Science [47]

- Improve

Hiring

- Productivity, prominence, and the effects of academic environment [48]

- Minimizing the Influence of Gender Bias on the Faculty Search Process [49]

- An evidence-based faculty recruitment workshop influences departmental hiring practice perceptions among university faculty [50]

- Searching for a Diverse Faculty: What Really Works. [51]

- Does the Gender Composition of Scientific Committees Matter? [52]

- Gender Quotas in Hiring Committees: A Boon or a Bane for Women? [53]

- The achievement of gender parity in a large astrophysics research centre [54]

- Increasing diversity in STEM academia: a scoping review of intervention evaluations [55]

- Can mentoring help female assistant professors in economics? An evaluation by randomized trial [56]

- Reducing discrimination against job seekers with and without employment gaps [57]

- Les inégalités de genre dans les carrières académiques : quels diagnostics pour quelles actions ? [58]

- Do Rubrics Live up to Their Promise? Examining How Rubrics Mitigate Bias in Faculty Hiring [59]

- How to improve gender equality in the workplace [60]

- Value of diversity

- Stereotypes

and bias (in and beyond academia)

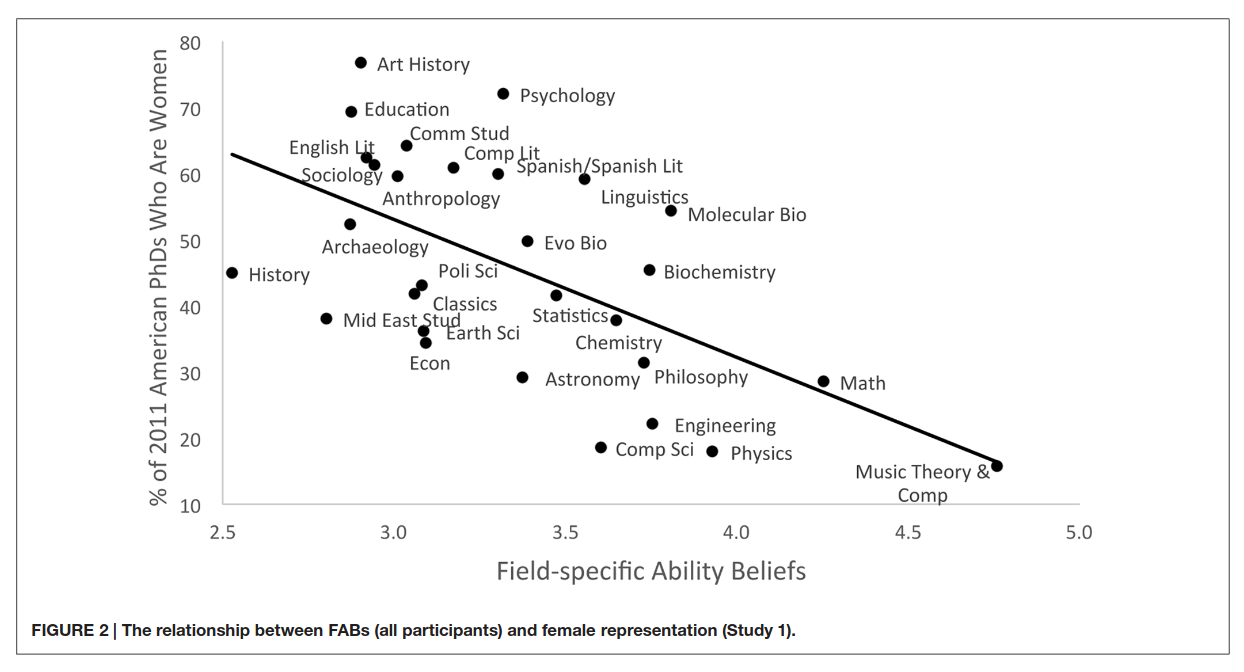

- Women are underrepresented in fields where success is believed to require brilliance [61]

- An Emphasis on Brilliance Fosters Masculinity-Contest Culture [62]

- The Development of Children’s Gender Stereotypes About STEM and Verbal Abilities: A Preregistered Meta-Analytic Review of 98 Studies [63]

- How Preschoolers Associate Power with Gender in Male-Female Interactions: A Cross-Cultural Investigation [64]

- Looking Deathworthy: Perceived Stereotypicality of Black Defendants Predicts Capital-Sentencing Outcomes [65]

- Against the star culture in math/CS

- Just some brain breaking illusions

- Bibliography in Progress

- References

For a variety of subjects, this page very quickly summarizes and cite some reports and publications, as well as some statistics computed and compiled for this overall project.

Gender and sexual harassment

Ireland COSHARE North-South survey report [1]

Survey on 521 staff members in Irish Higher Education:

- “Almost two thirds of participants (64%) had experienced sexual harassment in the past five years. This included 57% who had experienced sexist hostility, 23% with an experience of electronic or visual sexual harassment, 34% who experienced sexualised comments, 31% who had experienced unwanted sexual attention, and 5% with an experience of sexual coercion.”

- “A striking finding was that, for most participants who were affected, harassment was experienced in both personal and professional contexts”

- “(26%) experienced some form of sexual violence in the past five years, in their personal or professional lives” (half of those, 13%, at the workplace)

On general well-being: “The PHQ-4 measure of anxiety and depression demonstrated widespread mental health burden among the participant group as a whole. Those with previous experience of SVH had significantly higher scores than other survey respondent”

National Surveys of Staff and Student Experiences of Sexual Violence and Harassment in Irish HEIs [2] [3]

11, 417 responses were received (7,901 students and 3,516 staff).

Staff:

- “half of the respondents described being treated differently (52%) or being put down or condescended to (47%) because of gender. Approximately one third of the respondents (35%) said they had experienced sexist remarks.”

- “sexual hostility or crude gender harassment was described by between 14% and 21% of the survey respondents”

- “6% of survey respondents said someone had continued to ask them for a romantic date even though they had said ‘no’ and 10% had the experience of someone making unwanted attempts to establish a romantic sexual relationship with them”

- ” coercive harassment ranged from 1% (retaliation after a relationship ended), to 2% (implying better treatment) and 3% (feeling threatened, feeling bribed with a reward).”

- ” most common form of unwanted sexual contact was being touched in a way that made them feel uncomfortable (12%).”

- “someone making unwanted attempts to stroke or kiss the person. This was described by 4% of staff”

Students:

- half experience gender harassment, a third sexual hostility

- “Nearly three in ten of the students who responded to the survey said they felt like they were being bribed with a reward or special treatment to engage in sexual behaviour, and 27% responded that someone had implied better treatment if they were sexually cooperative.”

- “non-consensual sexual touching without any indication that the behaviour was welcome (45% of students overall)”

- “Nearly one in five (19%) of the females who responded to these statements described experiencing non-consensual vaginal penetration through coercion, while 31% had this experience while incapacitated, forced, or threatened with force.”

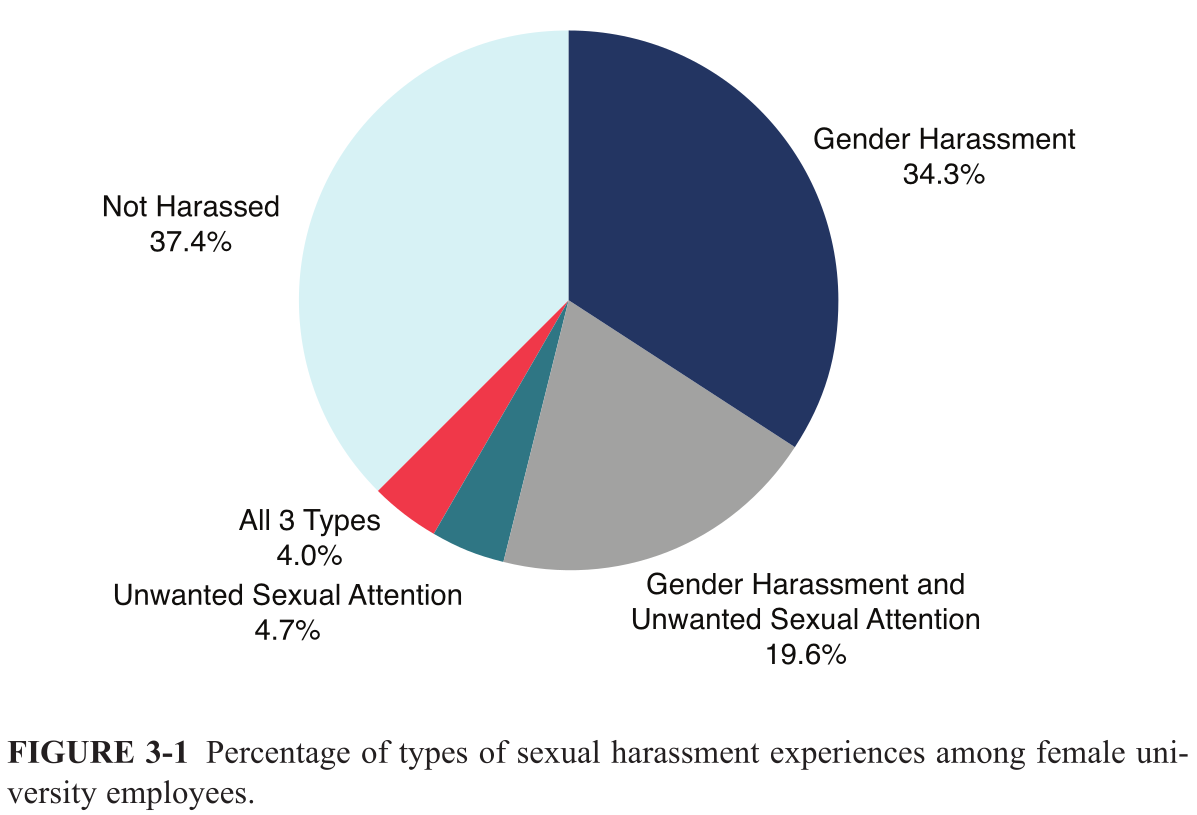

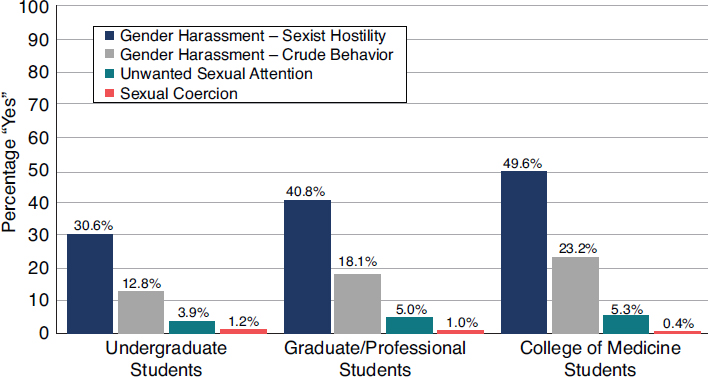

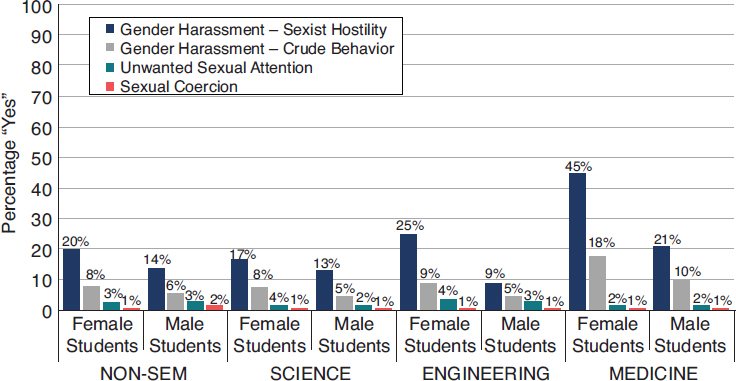

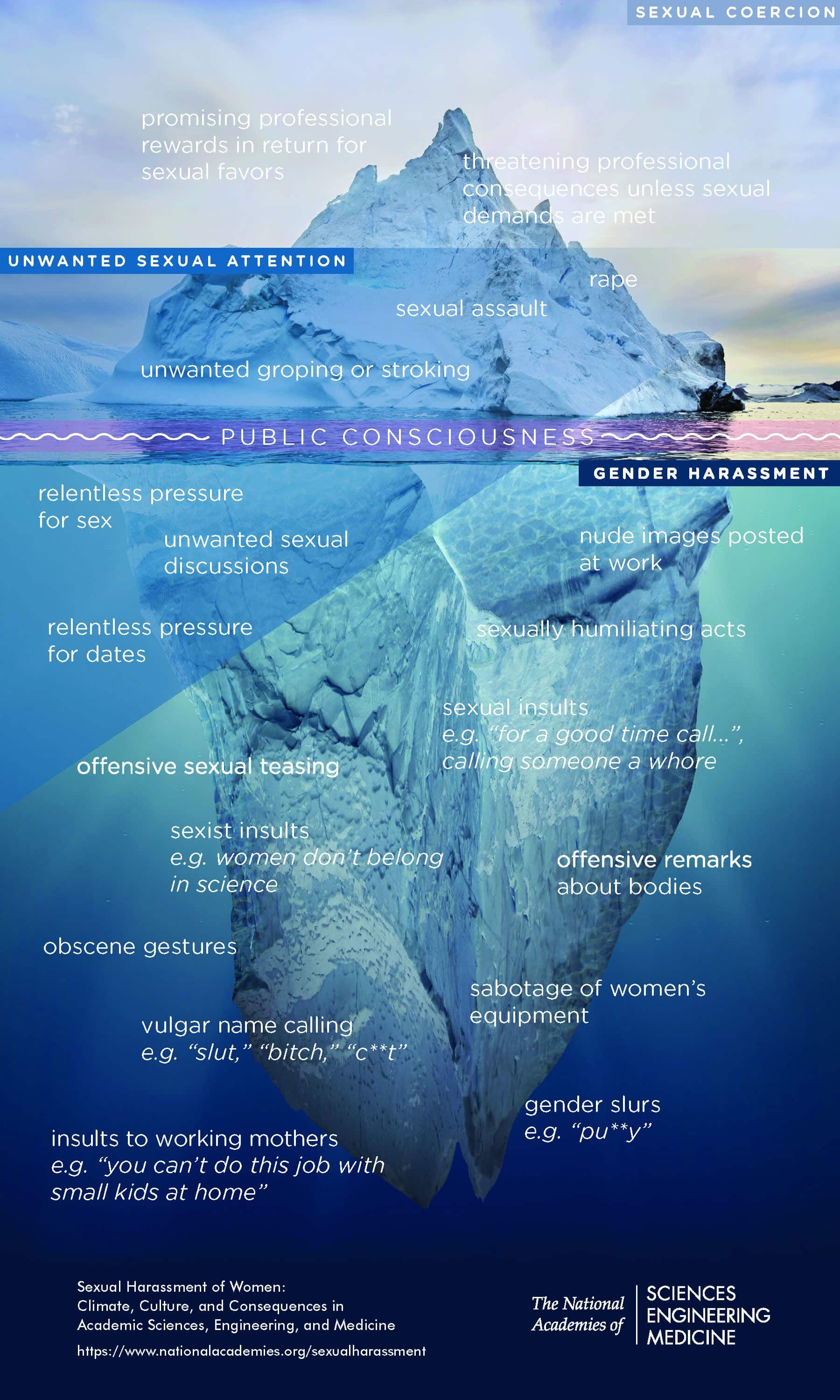

Sexual harassment of women: Climate, culture, and consequences in academic sciences, engineering, and medicine [4]

A massive consensus study report from the US national academies of sciences, engineering and medecine.

“the academic workplace (i.e., employees of academic institutions) has the second highest rate of sexual harassment at 58 percent (the military has the high- est rate at 69 percent) when comparing it with military, private sector, and the government”

“Greater than 50 percent of women faculty and staff and 20–50 per- cent of women students encounter or experience sexually harassing conduct in academia.”

“the most potent predictor of sexual harassment is organizational climate—the degree to which those in the organization perceive that sexual harassment is or is not tolerated.”

“The environments in which the power structure of an organization is hierarchical with strong dependencies on those at higher levels or in which people are geographically isolated are more likely to foster and sustain sexual harassment.”

It is a full chain supporting the worst.

“sexual coercion never took place without unwanted sexual attention and gender harass- ment.”

Facts are too often ignored: “The interview responses demonstrate that the behavior of male colleagues, whom higher-ranking faculty or administrators perceived as “superstars” in their par- ticular substantive area, was often minimized or ignored.”

Big difference when asking: “A meta-analysis of sexual harassment surveys demonstrates that the prevalence rate is 24 percent when women are asked whether they have experienced “sexual harassment” versus 58 percent when they are asked whether they experienced harassing behaviors that meet the definition of sexual harassment (and are then classifi d as such in the analysis)”

“Gender harassment has adverse effects. Gender harassment that is severe or occurs frequently over a period of time can result in the same level of negative professional and psychological outcomes as isolated instances of sexual coercion. Gender harassment, often considered a “lesser,” more in- consequential form of sexual harassment, cannot be dismissed when present in an organization. The greater the frequency, intensity, and duration of sexually harassing behaviors, the more women report symptoms of depression, stress, and anxiety, and generally negative effects on psychological well-being. The more women are sexually harassed in an environment, the more they think about leaving, and end up leaving as a result of the sexual harassment.”

Following the law is not enough! “Even though laws have been in place to protect women from sexual harass- ment in academic settings for more than 30 years, the prevalence of sexual harass- ment has changed little in that time.”

“A systemwide change to the culture and climate in higher education is required to prevent and effectively address all three forms of sexual ha- rassment.”

“Anti–sexual harassment training programs should focus on changing behavior, not on changing beliefs. Programs should focus on clearly communicating behavioral expectations, specifying consequences for failing to meet these expectations, and identifying the mechanisms to be utilized when these expectations are not met. Training programs should not be based on the avoidance of legal liability.”

bystander training: “Academic institutions should utilize training approaches that develop skills among participants to interrupt and intervene when inappropriate behavior occurs.”

“Reducing hierarchical power structures and diffusing power more broadly among faculty and trainees can reduce the risk of sexual ha- rassment”

“Systems and policies that support targets of sexual harassment and pro- vide options for informal and formal reporting can reduce the reluctance to report harassment as well as reduce the harm sexual harassment can cause the target.”

“Transparency and accountability are crucial elements of effective sexual harassment policies.”

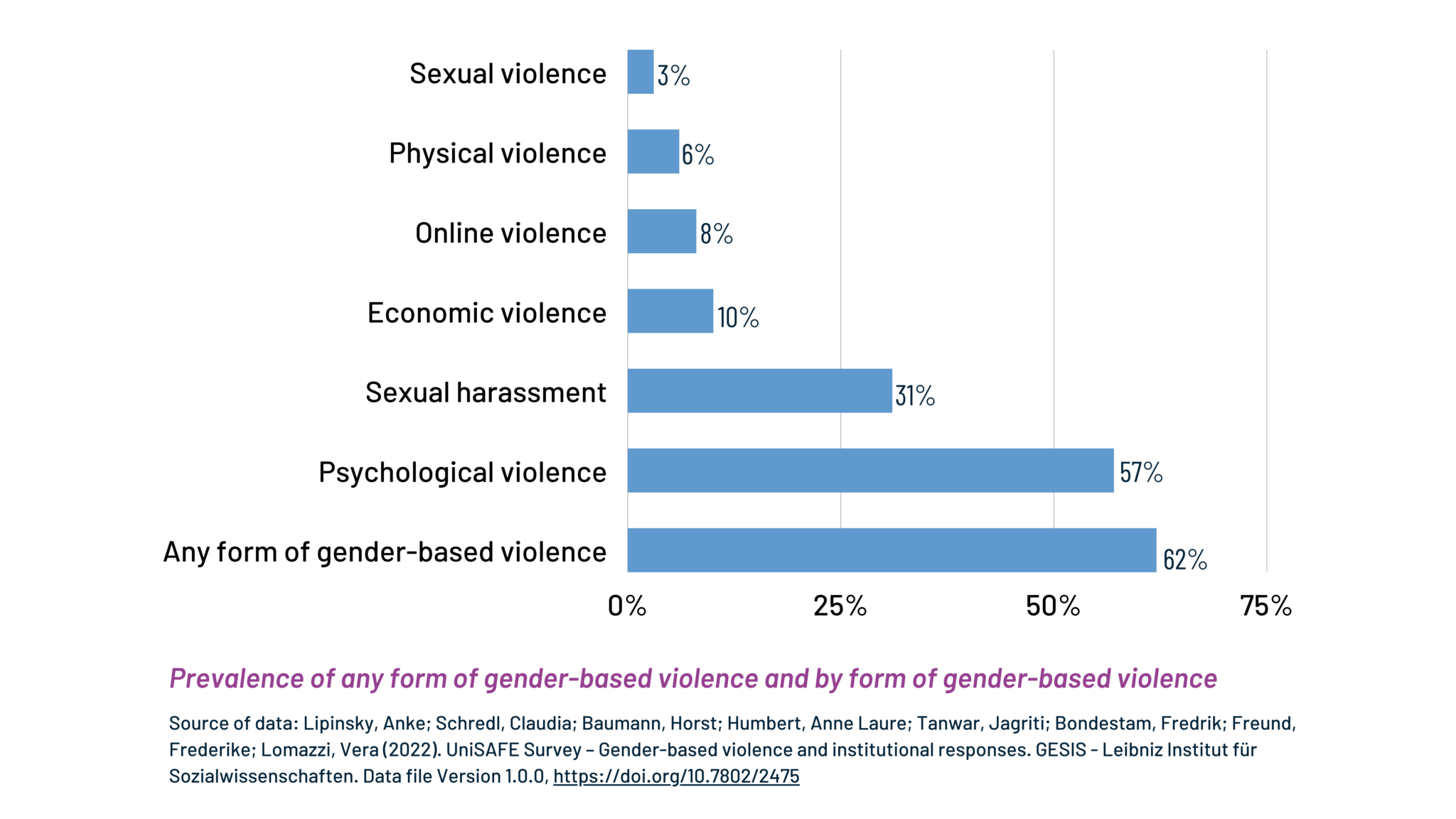

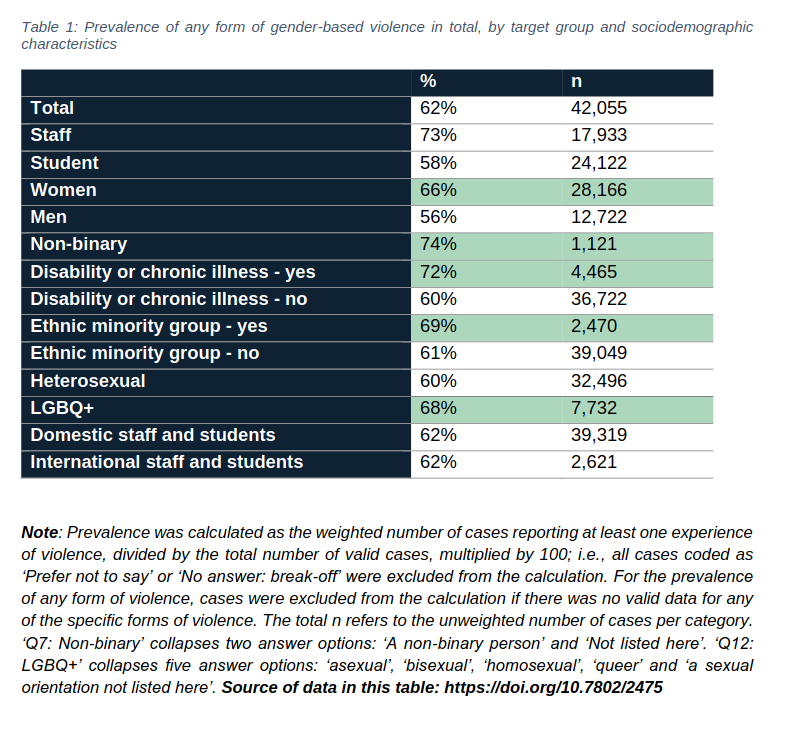

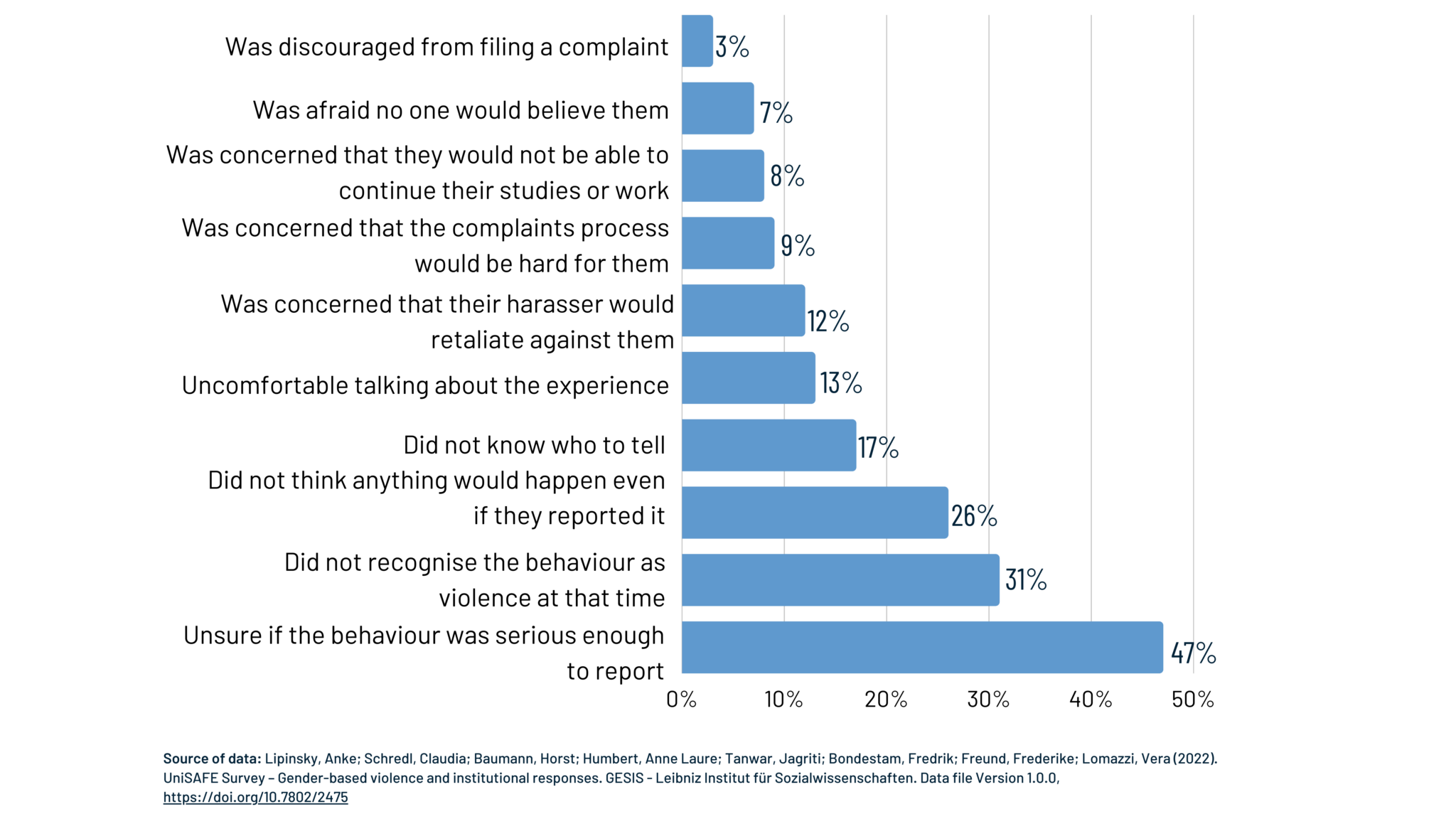

Gender-based violence and its consequences in European Academia [5]

Big survey of over 42 186 staff and students. “Gender-based violence is understood as violence directed towards a person because of their gender, or violence that affects persons of a specific gender disproportionately. The forms of gender-based violence considered by the UniSAFE survey are based on the four forms outlined in the Council of Europe’s Istanbul Convention (2011), that is, violence that can be physical, sexual, psychological, or economic.”

“62% of the survey respondents have experienced at least one form of gender-based violence”

Many groups are more likely to be targetted:

“only 13% reported it”

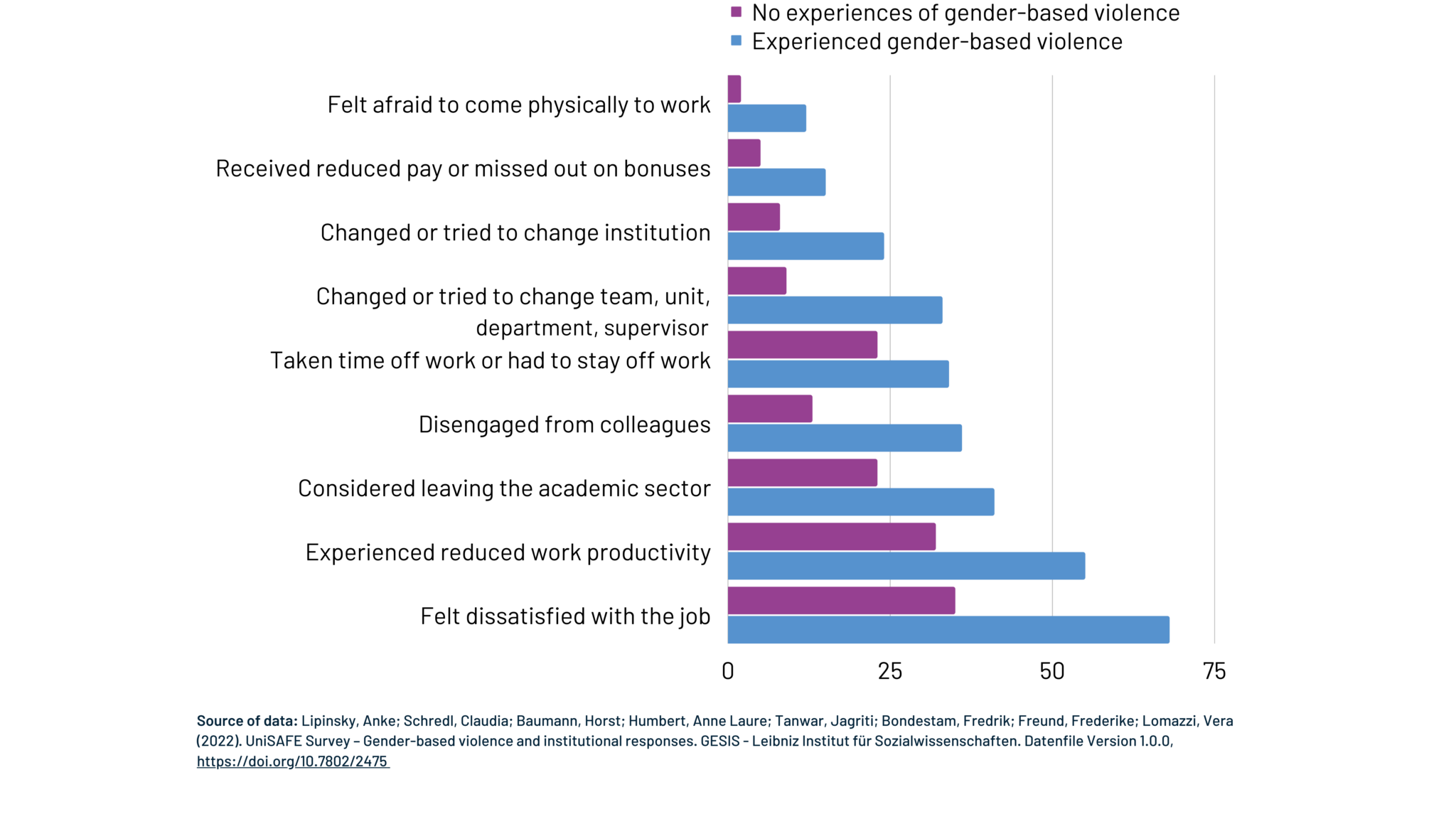

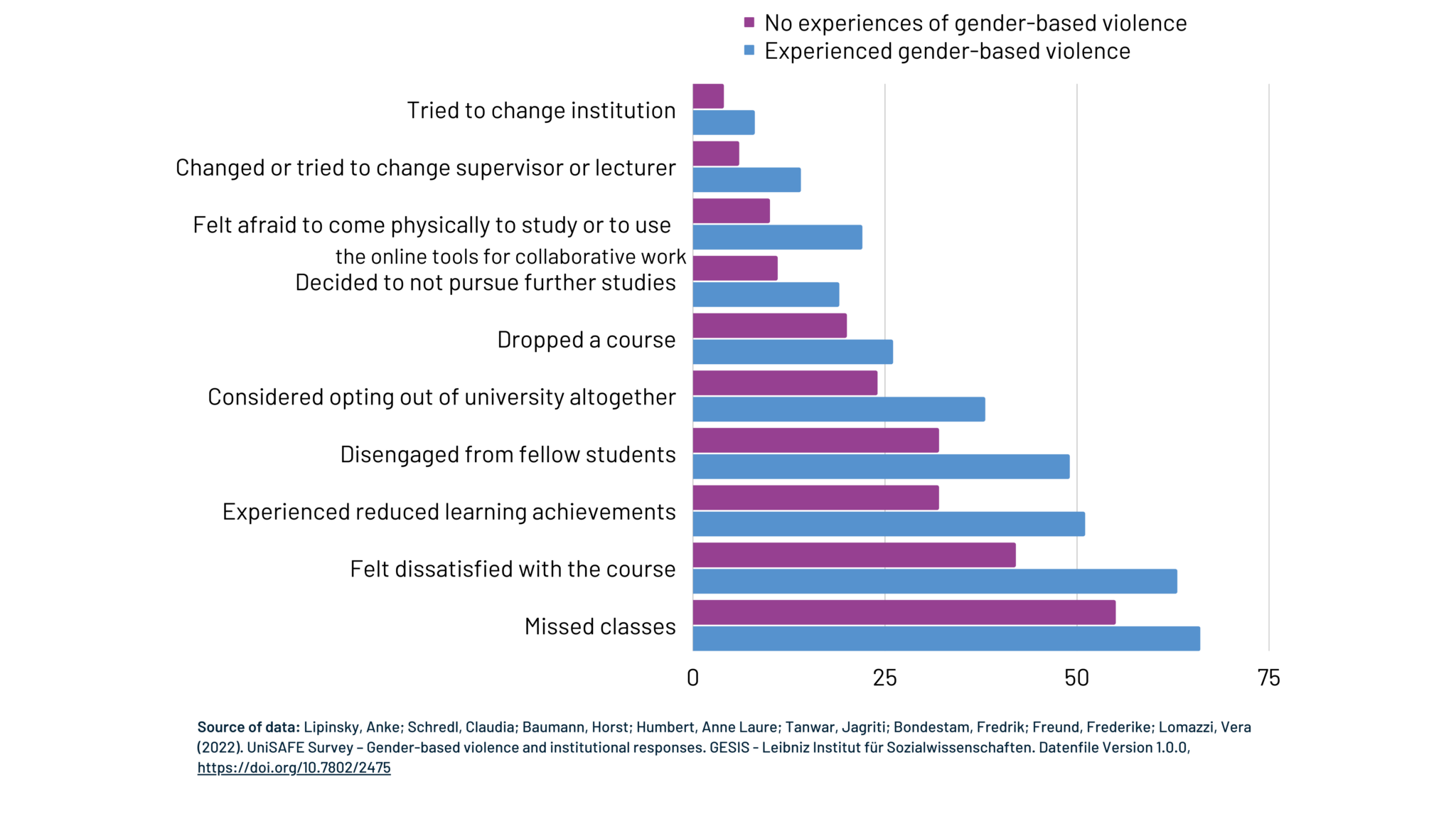

For staff, their are many work-related consequences

Or for students, study-related consequences

Violences sexuelles dans l’enseignement supérieur en France : un focus sur l’alcool et le cannabis [6]

Rapport sur une enquête nationale menéee en 2023-2024, 67 000 répondants:

- “Depuis leur arrivée dans l’enseignement supérieur, 24 % des femmes, 9 % des hommes et 33 % des transgenre/non binaire/queer ont subi au moins une forme d’agression sexuelle ou de viol (ou tentative), souvent réitérée.”

- “Selon les types de violences concernés (tentative d’agression sexuelle, agression sexuelle, tentative de viol ou viol), les étudiantes sont de 2.7 à 4.5 fois plus fréquemment victimes que les étudiants.”

- “23.8 % des étudiantes déclarent avoir subi une tentative d‘agression sexuelle, 18.7 % une agression sexuelle, 3.8 % une tentative de viol et 5 % un viol” (vs 1,1% de viol pour les hommes)

- “Plus de la moitié des violences sexistes et sexuelles (VSS) en milieu étudiant implique une consommation d’alcool.”

- “Dans 90 à 95% des cas, quelles que soient les violences subies, les auteurs désignés sont de sexe masculin”

- En informatique, on est à 30% de taux de victimation pour les étudiantes.

Keywords: statistics, sexual assault, rape, alcool, france

The Potential of Sexual Consent Interventions on College Campuses: A Literature Review on the Barriers to Establishing Affirmative Sexual Consent [7]

There are rape myths: “In the case of sexual consent, three rape myths are relevant to the new affirmative consent law: (a) unintentional sexual behavior occurs, (b) miscommunication about sexual behavior happens, and (c) rape does not occur in a preexisting sexual relationship.”

They are myths:

- “Ultimately, reported accidental or unintentional intercourse results from coercive behavior and a lack of sexual consent. The findings of this research undermine the rape myth suggesting that the perpetrator did not mean to commit rape.”

- “This body of research about sexual communication demonstrates that miscommunication cannot be blamed for sexual assault occurring”

- ” majority of women are sexually assaulted by an acquaintance”

Sexual scripts are created by medias and culture:

- “A sexual script represents the cognitive schema of the normative progression of events in a sexual encounter”

- “readers of men’s magazines reported lower intentions to ask for sexual consent, as well as lower intentions to respect their partners’ sexual consent decisions”

We need to focus on broad cultural change: “Sexual communication, as discussed in this article, is shaped by sociocultural issues such as sexual scripts, gender roles, and rape myths (Murnen et al., 2002). Interventions that support broader cultural change are needed (Jozkowski & Humphreys, 2014; Murnen et al., 2002). If affirmative consent were to become the new social norm, students may change to express more favorable attitudes towards affirmative consent, change their sexual communication to actively engage in affirmative consent, and reduce the prevalence of sexual assault.”

Keywords: sexual scripts, culture, rape myths

Sciences : où sont les femmes ? [8]

Culture change: “L’idée impropre du bienfait de la compétition et de l’instabilité des postes pour promouvoir la production scientifique des jeunes est à proscrire et cela bénéficiera aux femmes, comme aux hommes.”

Bias: “Sentiment de réussite aux évaluations selon le genre : Indépendamment de leurs performances, le sentiment de réussite aux évaluations est toujours inférieur pour les filles que pour les garçons, cet effet s’amplifiant entre la classe de 6e et la classe de seconde”

Pressions, silence et résistances - Étude sur les violences sexistes et sexuelles et les discriminations en milieu doctoral en France [9]

Survey of 2100 French PhD students.

“Les femmes et les minorités de genre sont toujours surreprésentées parmi les victimes : 27,5 % des femmes rapportent des violences sexistes dans leur laboratoire, contre 15,7 % des hommes. Les agressions sexuelles sont signalées par 7,1 % des femmes en congrès et par 1,1 % dans le cadre du laboratoire.”

“les auteurs des violences sont majoritairement des hommes (83,3 %)”

“Plus de la moitié des répondant·es (50,8 %) considèrent que les femmes voient leur place constamment remise en cause”

“la maternité représente un obstacle plus important au doctorat que la paternité. Parmi les répondant·es, 80,4 % estiment qu’il est difficile d’être mère lors de son doctorat, contre 49,2 % pour les pères.”

“la majorité des répondant·es considère que les mesures de prévention des VSS sont aujourd’hui encore insuffisantes”

“66,9 % des victimes d’agressions n’ont effectué aucun signalement et environ 24 % des répondant·es ayant signalé ces violences rapportent un manque de soutien ou des réactions inadéquates.”

Impact of the undressing consent program [10]

A US university, reports on training on consent, with a 90 minute dedicated training, with which students are very satisfied and yields change:

- “Since 2021, Huron and King’s have invested in enhanced efforts to prevent sexual violence on campus through the delivery of a 90-minute, live-facilitated, interactive prevention program titled”Undressing Consent.””

- “Almost 90% of the students were satisfied with Undressing Consent. They found it to be important and valuable.”

- “Most female and non-binary students reported high level of comfort in having conversations about desires and boundaries despite retrospectively reporting that Undressing Consent helped them better communicate their boundaries.”

- “The program was found to help navigate the transition to university and led to some changes in student knowledge and attitudes about consent.”

Keywords: consent, student training

Effects of Mandatory Sexual Misconduct Training on University Campuses [11]

“Our surprising finding is that training makes women less likely to say that they would report sexual assault. In all three studies, participating in training is associated with a large and highly statistically significant drop in the share of women who affirm that, if they were sexually assaulted by another student, they would be “very likely” or “somewhat likely” to report the experience to the university. Although our study was not designed to systematically explore the reasons for the drop in reporting intentions, we speculate about it on the basis of interview material and responses to other survey questions. We suggest that training may aggravate women’s perceptions of the social risks involved in reporting. Women students resist labeling their experiences as assault and categorizing their sexual relationships as nonconsensual or coercive in the ways portrayed by training”

” The training produces some small positive effects: students gain broader definitions of sexual misconduct and are less likely to endorse common rape myths, and women students express less sexist attitudes immediately after training.”

Keywords: sexual assault, negative effect of training, fear of consequecnes

Looking for a preventive approach to sexual harassment in academia. A systematic review [12]

“The findings confirm that academia is a breeding ground for SH due to power imbalances and that vulnerabilities related to the macro-dynamics of power, social and cultural inequalities are risk factors for SH. It is recommended that SH prevention interventions in academia 1. adopt a socio-ecological perspective; 2. include evidence-based programs such as those dedicated to bystanders; 3. are integrated with each other through valuable networking and multistakeholder involvement and 4. pay attention to support com- plaints, victim listening and intake activitie”

On bystander programs: “Like several previously presented training and projects, bystander programs can be transversal and situated between the individual, interpersonal, and contextual levels (Ban- yard, 2011); these programs focus on recognizing early signs of sexually harmful behav- ior and developing skills to intervene. Within this framework, bystander programs play an important role in raising community awareness and creating “guardians” who can prevent certain forms of SH and/or offer support to victims. The research conducted confirms that after participating in bystander intervention training, faculty staff also felt that they could play a crucial role in preventing violence by modeling prosocial behavior, seeking to be perceived as allies by students, and challenging cultural norms related to SV (Robinson et al., 2020)”

Interventions must adopt a socio-ecological perspective: “On a more conceptual level, some research emphasizes the need to always con- sider gender-based violence as a problem related to social inequalities and to highlight the close connection between multiple structural forms of oppression when designing interventions (Atkinson & Standing, 2019; Banner et al., 2022; Hurtado, 2021).”

Keywords: sexual harassment, bystander training, power

Association Between Sexual Harassment Intervention Strategies and the Sexual Harassment Perception and Attitude of University Students in Beijing, China [13]

A bad perception of universities willingwness to act may undermines training effect: “Education, training, and publicity programs are key to addressing the issue of sexual harassment on campuses (Cleary et al.,1994; de Lijster et al., 2016; Erinosho et al., 2021). Positive associations between informal education activ- ities, multiformat publicity, and female students’ intolerant attitudes toward sexual harassment were also observed in this study. However, prevention mechanisms were negatively associated with intolerant attitudes toward sex- ual harassment. Informal education activities and multiformat publicity appear to be positive strategies. There may be some problems with the design, opera- tion, or other aspects of sexual harassment prevention mechanisms that con- tribute to the negative impact on students’ attitudes toward sexual harassment. This would appear to be partly explicable in terms of futility in university prevention mechanisms. To protect their reputations, some universities remain silent, refuse to inform the public about the process and outcomes, and punish harassers too lightly (Lay, 2019; Lichty et al., 2008; Robertson et al., 1988).”

Keywords: opaque report processes, training

Can I Say “No”? How Power Dynamics Hinder Consent in University Settings [14]

” Restricting the notion of sexual consent to its communicative dimension risks perpetuating rape myths and victim-blaming, placing undue blame on victims who have “failed to properly communicate.” Additionally, the influence of unequal power dynamics and gendered and social norms need to be addressed when dis- cussing consent and sexual violence. Consent education, including affirmative consent and grey area trainings, remains important (Setty, 2023) and should incorporate chal- lenges to social norms (e.g., heteronormative standards, gender-based power imbalances such as expectations of male assertiveness and female compliance) and support the iden- tification of conditions that render consent invalid (e.g., intoxication, coercion, position of authority). The normalization of misconduct in supposedly safe environments and the issue of institutional betrayal highlight the need for institutional change and courage. Universities must promote cultural change, challenge social norms, and ensure transpar- ency and accountability to rebuild trust”

Discriminations

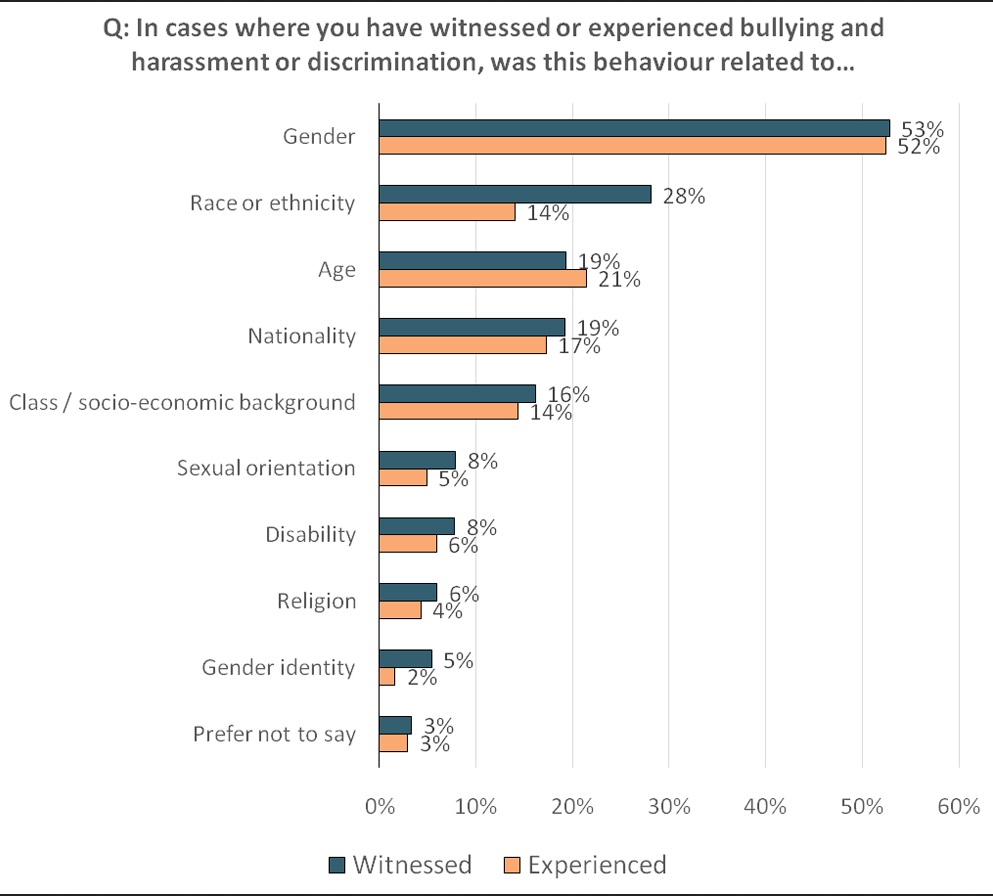

Understanding Research Culture: What researchers think about the culture they work in [15]

For UK researchers, 94 qualitative interviews and a quantitative e-survey with 4267 usable responses.

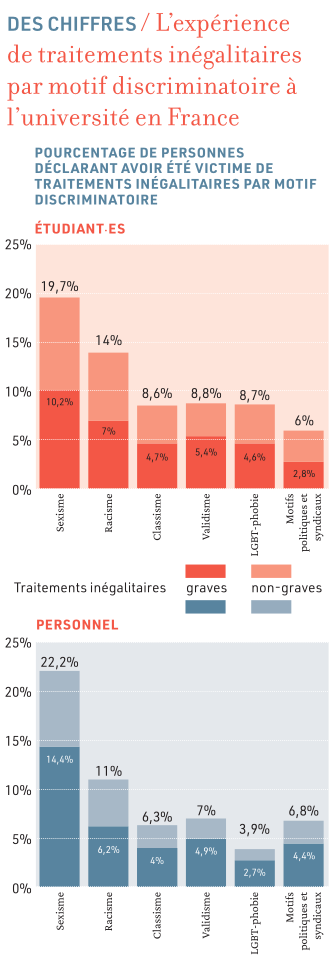

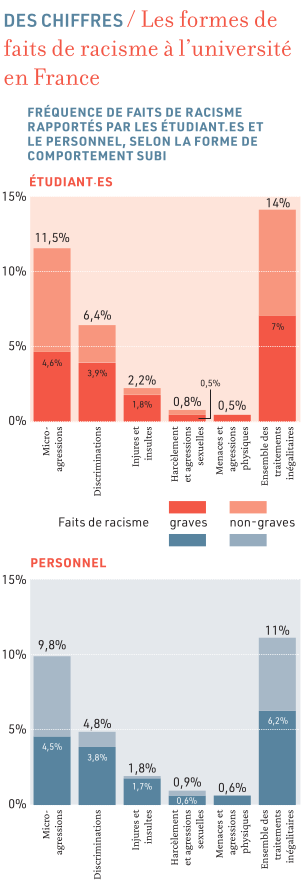

QUELLES POLITIQUES POUR RÉPONDRE AUX DISCRIMINATIONS À L’UNIVERSITÉ ? [16]

Based on ACADISCRI study, 4 FR universities, over 10k answers.

“14 % des étudiant·es et 11 % des salarié.es des universités enquêtées déclarent avoir subi des faits de racisme, dont plus de la moitié sont estimés graves. Plus encore, les personnes racisées ― c’est-à- dire traitées comme membres d’un groupe racial minoritaire ― sont plus de 33 % à déclarer avoir vécu au cours de leurs études ou de leur carrière des traitements inégalitaires racistes.”

“L’enquête ACADISCRI montre que les traitements discriminatoires validistes affectent 8,8 % des étudiant·es et 7 % du personnel des universités enquêtées dans leur ensemble.”

Power structures: “L’enquête ACADISCRI montre ainsi que, parmi les groupes racisés, les doctorant·es déclarent presque deux fois plus de discrimination que les étudiant·es, et approximativement entre trois et quatre fois plus que les diverses catégories de personnels.”

“À l’opposé, une politique antidiscriminatoire devrait être une politique délibérément “inclusive et démocratique” prenant à bras le corps le problème des inégalités, des rapports de pouvoir et des hiérarchisations sociales – toutes choses qui struc- turent en profondeur l’enseignement supérieur et la recherche. Ce devrait être une politique qui met en question les dynamiques de concurrence et de classement qui structurent l’espace académique (dont la psychologie sociale montre qu’elle renforce les discriminations), qui s’attaque à transformer les normes qui régissent le fonctionnement habituellement inégalitaire des institutions, et qui reconnaît pleinement l’expertise des groupes minoritaires quant à la manière dont opèrent concrètement les rapports de domination dans l’enseignement supérieur.”

Gender discrimination in academia

The gender citation gap: Approaches, explanations, and implications [17]

Women publish less, but are cited as much per paper: ” I show that articles written by women receive comparable or even higher rates of cita- tions than articles written by men. However, women tend to accumulate fewer citations over time and at the career level. Contrary to the notion that women are cited less per article due to gender-based bias in research evaluation or citing behaviors, this study suggests that the primary reason for the lower citation rates at the author level is women publishing fewer articles over their careers.”

When Two Bodies Are (Not) a Problem: Gender and Relationship Status Discrimination in Academic Hiring [18]

“Drawing from gendered scripts of career and family that present men’s careers as taking precedence over women’s, committee members assumed that heterosexual women whose partners held academic or high-status jobs were not “movable,” and excluded such women from offers when there were viable male or single female alternatives. Conversely, committees infrequently discussed male applicants’ relationship status and saw all female partners as movable. Consequently, I show that the “two-body problem” is a gendered phenomenon embedded in cultural stereotypes and organizational practices that can disadvantage women in academic hiring.”

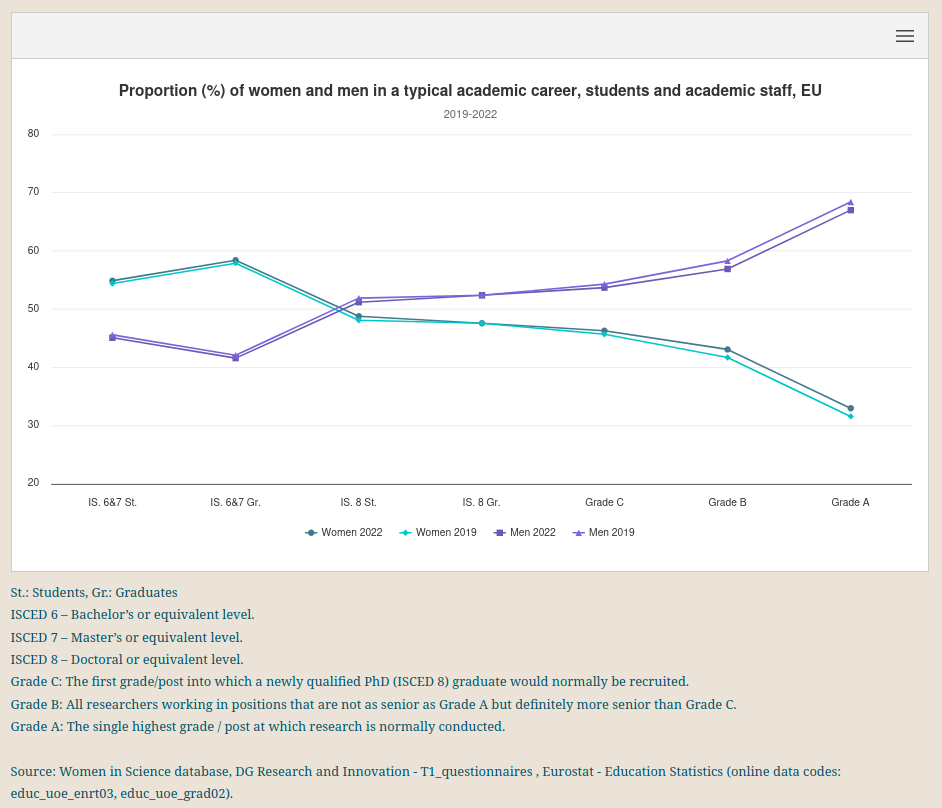

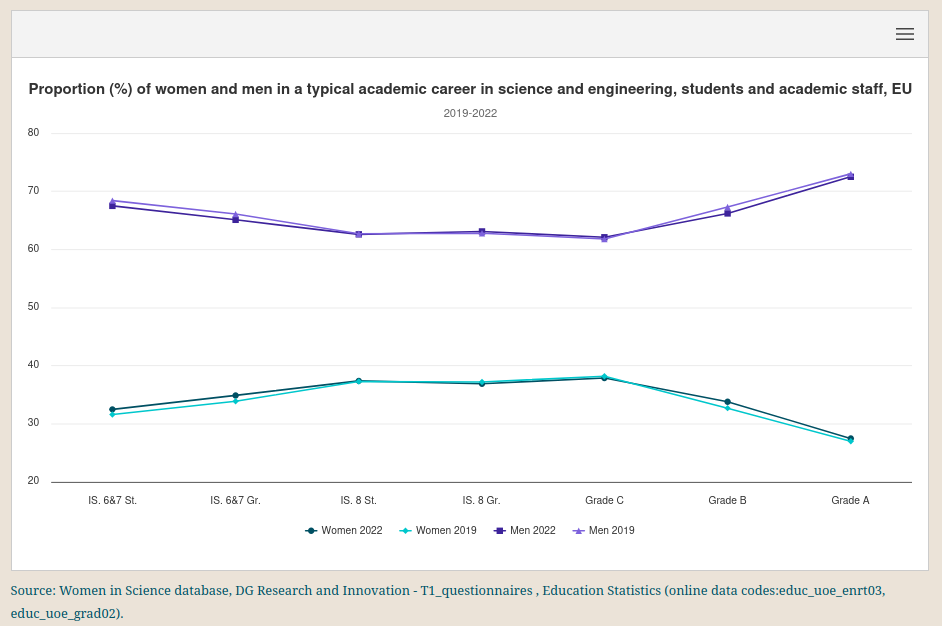

SHE Figures 2024 [19]

The leaky pipeline is everywhere:

In STEM, we start from a worth position:

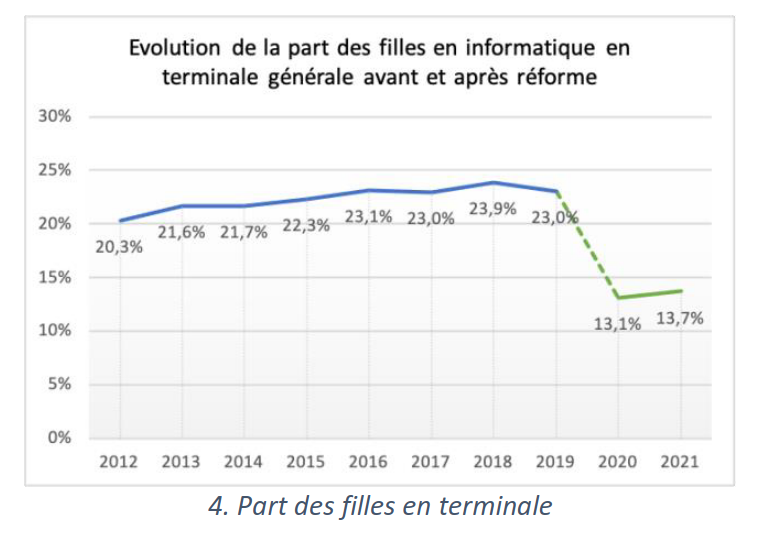

Impact de la réforme du lycée sur l’enseignement de l’informatique : bilan et perspectives [20]

Very bad impact of a french 2019 highschool reform on share of women in computer science teaching.

Gendered Citations at Top Economic Journals [21]

“This paper investigates how women’s works are perceived among their peers. I construct a dataset using bibliographic data from articles published in top journals in economics and granular information on the articles that cite them. I find that female-authored papers in top economic journals are (i) more likely to be cited outside economics, (ii) less likely to be cited by top-tier journals, and (iii) less likely to be cited by men. I conclude with a discussion on those results and their implications for females in economics.”

Recognition for Group Work: Gender Differences in Academia [22]

Women don’t get any credit for group work, while men

do:

“How is credit for group work allocated when individual contributions

are not observed? I use data on academics’ publication records to test

whether demographic traits like gender influence how credit is allocated

under such uncertainty. While solo-authored papers send a clear signal

about ability, coauthored papers are noisy, providing no specific

information about each contributor’s skills. I find that men are tenured

at roughly the same rate regardless of coauthoring choices. Women,

however, are less likely to receive tenure the more they coauthor. The

result is much less pronounced among women who coauthor with other

women.”

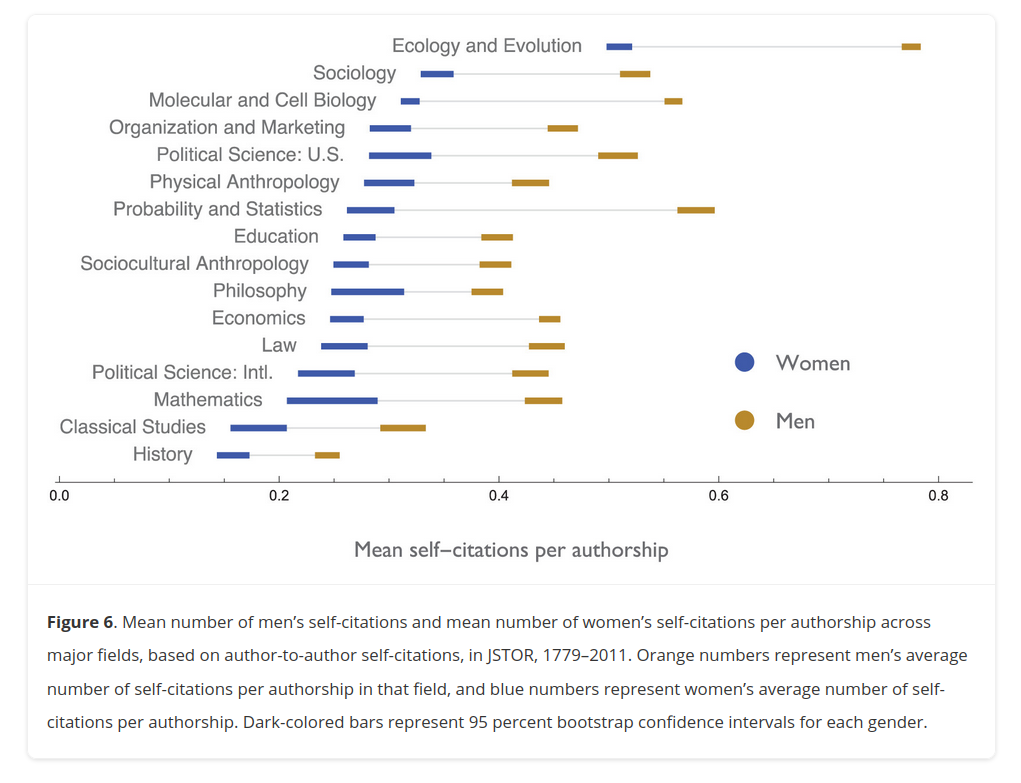

Men set their own cites high: Gender and self-citation across fields and over time [23]

“In the last two decades of data, men self-cited 70 percent more than women.”

Gender Inequality and Time Allocations Among Academic Faculty [24]

For a US survey around 1999, with 12,510 full-time faculty members: “(1) women faculty members prefer to spend a greater percentage of their time on teaching, while men prefer to spend more time on research, although these preferences are themselves constrained; (2) women faculty members spend a greater percentage of their workweek on teaching and a smaller percentage on research than men, gaps that cannot be explained by preferences or educational and institutional attributes; and (3) women faculty members have larger time allocation mismatches than men—that is, their actual time allocations to both teaching and research diverge more from their preferred time allocations than those of men.”

Asked More Often: Gender Differences in Faculty Workload in Research Universities and the Work Interactions That Shape Them [25]

“Similar to past studies, we found women faculty spending more time on campus service, student advising, and teaching-related activities and men spending more time on research. We also found that women received more new work requests than men and that men and women received different kinds of work request.”

Precise time-diary from study on “associate and full professors in 13 universities that are members of the Big 10 Conference”, around 100 people.

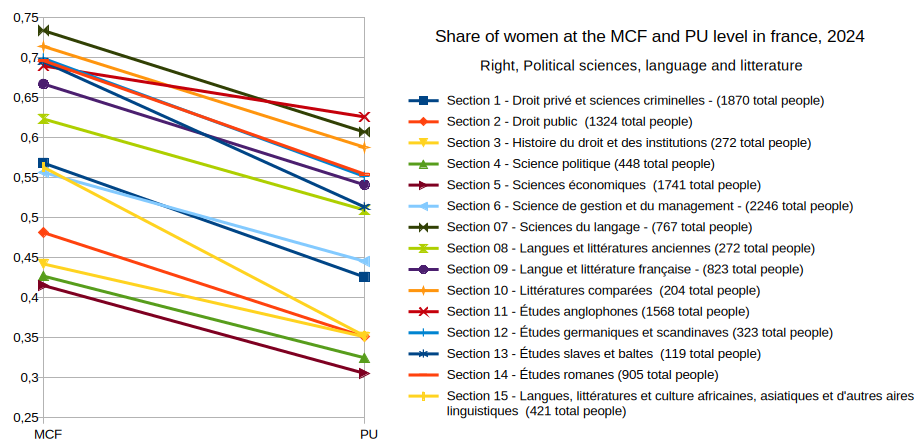

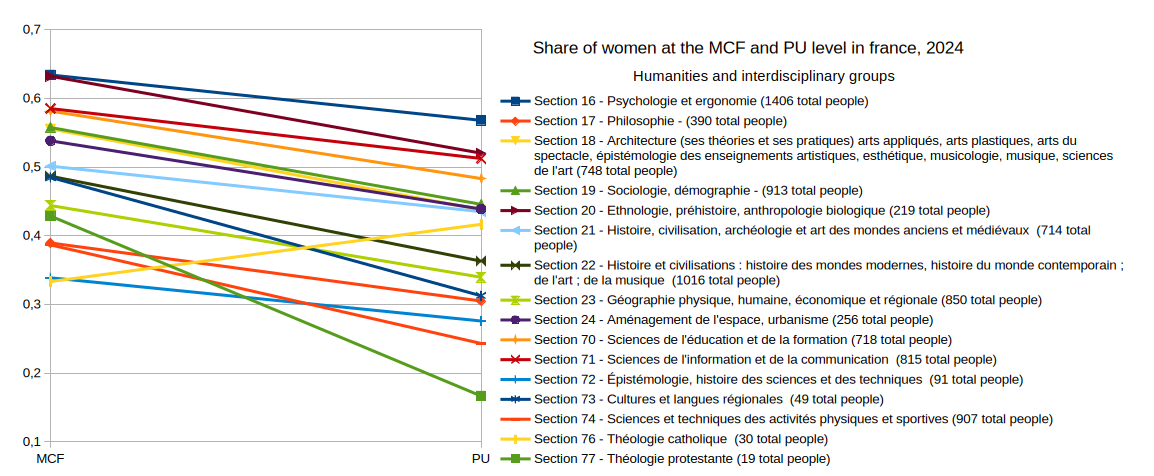

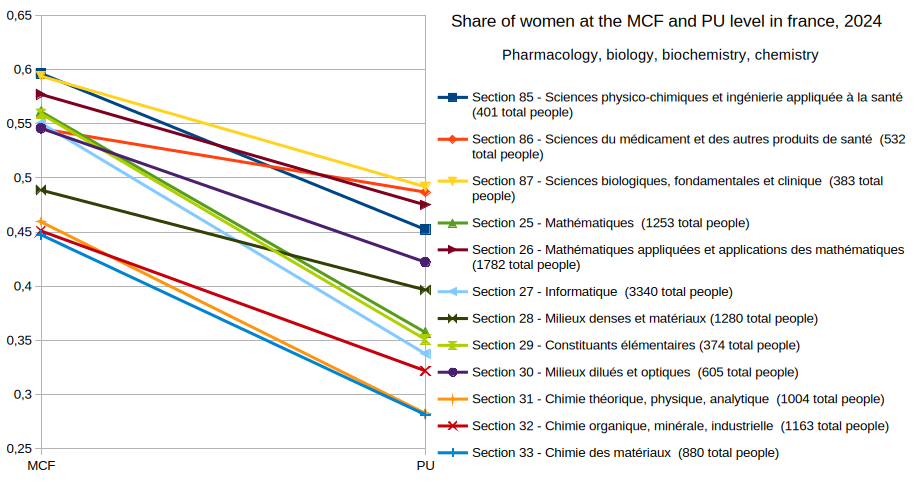

Leaky pipeline at the full professor level in France

Across all disciplines, the share of women at the full professor level is smaller than the one at assistant professor level. (actually, there is one exception out of 56 “CNU sections” but it only comprises 30 people)

Gender disparities in high-quality research revealed by Nature Index journals [26]

“Women are underrepresented at prestigious authorships compared to men (Prestige Index = -0.42). The underrepresentation accentuates in highly competitive articles attracting the highest citation rates, namely, articles with many authors and articles that were published in highest-impact journals.”

“Women publish fewer articles compared to men (39.0% female authors are responsible for 29.8% of all authorships) and are underrepresented at productivity levels of more than 2 articles per author. Articles with female key authors are less frequently cited than articles with male key authors. The gender-specific differences in citation rates increase the more authors contribute to an article. Distinct differences at the journal, journal category, continent and country level were revealed. The prognosis for the next decades forecast a very slow harmonization of authorships odds between the two genders.

Quality of evidence revealing subtle gender biases in science is in the eye of the beholder [27]

“demonstrated that men evaluate the quality of research unveiling this bias as less meritorious than do women.”

“these results suggest a relative reluctance among men, especially faculty men within STEM, to accept evidence of gender biases in STEM.”

The impact of gender on the review of the curricula vitae of job applicants and tenure candidates: A national empirical study [28]

Blind study with 238 male and female academic psychologists. CV with female name judged more harshly

The Queen Bee phenomenon in Academia 15 years after: Does it still exist, and if so, why? [29]

“Advanced career female academics are more likely than their male counterparts to underestimate the career commitment of women at the beginning of their academic careers.”

“Together, these studies show that the response pattern seen to characterize the ‘Queen Bee’ is not to be attributed to ‘the way some women are’ or how they typically interact with each other at work. Instead, research reveals that factors in the organizational context and more specifically the exposure to gender-stereotypical expectations, negative career experiences, and lack of organizational support contribute to the maintenance of the QB phenomenon”

Navigating the leaky pipeline: Do stereotypes about parents predict career outcomes in academia? [30]

Mock hiring experiment in academia. “The findings showed that parents were significantly less likely to be endorsed to be hired than non-parents, regardless of gender.”

Is there a motherhood penalty in academia? The gendered effect of children on academic publications in German sociology [31]

For sociologists in German academia: “Having children leads to a significant decline in the number of publications by women, while not affecting the number of publications by men.”

Do babies matter (Part II) [32]

Refering to their past study: “We found that men with”early” babies—those with a child entering their household within five years of their receiving the PhD—are 38 percent more likely than their women counterparts to achieve tenure”

Big survey of PhD students accross US: “One consistent finding across all nine campuses was that women were more than twice as likely as men to indicate that they had fewer children than they had wanted—a full 38 percent of women said so compared with 18 percent of men (see figure 5)”

“Women between thirty and fifty with children clock over a hundred hours each week on caregiving, housework, and professional responsibilities, compared with a little more than eighty-five for men with children”

Underrepresented minority (URM) discrimination

Underrepresented minority faculty in the USA face a double standard in promotion and tenure decisions [33]

“Data from five US universities on 1,571 faculty members’ P&T decisions show that URM faculty received 7% more negative votes and were 44% less likely to receive unanimous votes from P&T committees. A double standard in how scholarly productivity is rewarded is also observed, with below-average h-indexes being judged more harshly for URM faculty than for non-URM faculty.”

Weight discrimination

Weight bias in graduate school admissions [34]

“Higher BMI significantly predicted fewer post-interview offers of admission into psychology graduate programs. Results also suggest this relationship is stronger for female applicants. BMI was not related to overall quality or the number of stereotypically weight-related adjectives in letters of recommendation. Surprisingly, higher BMI was related to more positive adjectives in letters.”

Weight bias among students and employees in university settings: an exploratory study [35]

Study out of 292 students and 129 university employees: “Approximately half of the respondents reported experiencing weight-related stigma (44.7%), and half indicated holding prejudice towards overweight people (51.1%), with a moderate rate of bias according to the FPS (3.25).”

« L’unif ne veut pas de moi ! » La grossophobie en milieu académique au prisme du genre [36]

A lack of statistics in France:

- “En France, 17% de la population est classée « obèse » et 27-37% « en surpoids », selon l’indice de masse corporelle (IMC) (Carof 2021a, pp 59-60).”

- “Fondée sur des seuils d’IMC contestés, cette pathologisation privilégie la responsabilisation individuelle au détriment d’une lecture structurelle des inégalités sociales de santé (Carof 2019 ; 2021a, p 29).”

- “Ces discriminations se traduisent vraisemblablement par une sous-représentation des personnes grosses dans les carrières scientifiques, bien qu’il n’y ait pas de statistiques disponibles à ce sujet en Belgique ou en France.”

Statistics computations

To give a general idea, we compare the very simplified chances to become a professor/faculty/uni staff, based on some other characteristic (this is a simplified illustration, where all other things are considered equal and some numbers are approximated, some details on how we compute each chance is given afterward):

- men are 2.6 times more likely to

become PU : 28% of UK university prof are women [37], so

AdvMonF = 0,72/0,28 x 1 = 2.57. - somebody without a declared disability is

4.6 times more likely to become a uni staff: 4% of UK

uni staff have a declared disability, vs 16% of pop [38], so

AdvNotDisonDis = 0.96/.04 x .16/0.84. - a white person is 6.2 times more

likely to become a UK professor than a black person: in

UK, we have 18 770 White professor, 155 Black professor, 1495 Asian

professor, 295 Mixed, 340 Other, and 1755 others [37], so

0,7% of Black and 89% white for professor with known ethnicity, while

81.7% of the pop is white, and 4% is black, so

(

AdvWonB= 0.89/0.007 x 0.04/0.817) - somebody with a close relative with a PhD is

at least 2.4 times more likely to get a PhD: 20% of

french doctorates have a close relative with a phd [39], while only 1,15% of the population

has a thesis, and in France we have on average 1 brother, 2 parents, and

then maybe 2 uncle/aunts and 4 grand parents, so we have by counting

large at most 9 close relative in a family in france, so the chance to

not have a close relative with a thesis is at most

0,9885^9=0,90and we can say that less than 10% of the population has a close relative with a thesis (AdvPhDRelativeonNot= 0.20/0.8 x 0.95/0.10=4.75).

Given two groups A and B (e.g. male and female), the chance of a

member of group A to do X (e.g. become a prof) is

CA=(# of X in A)/(# of A), and similarly for B with

CB. The advantage AdvAonB of A over B, how

many times A has more chances to become X than B, is then

CA/CB. By putting together the equations, we get

AdvAonB= ((# of X in A)/(# of X in B)) x ((# of B)/(# of A)).

As the goal is to compute this from the respective share of A/B in X

(%A-X and %B-X or total population

(%A and %B), we simply multiply by the total

populations as needed, and

AdvAonB= ((# of X in A)/(# X) x (#X)/(# of X in B)) x (# of B)/(# population) x (# population)/(# of A))

and finally, AdvAonB= (%A-X/%B-X) x (%B/%A).

Toxic culture in general

Systematic review and meta-analysis of depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation among Ph. D. students [40]

“Among 16 studies reporting the prevalence of clinically significant symptoms of depression across 23,469 Ph.D. students, the pooled estimate of the proportion of students with depression was 24%”

“Available data suggest that the prevalence of depressive and anxiety disorders in the general population ranges from 5 to 7% worldwide . In”

“disorder among young adults have ranged from 13% (for young adults between the ages of 18 and 29 years in the 2012–2013 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III 71 ) to 15% (for young adults between the ages of 18 and 25 in the 2019 U.S. National Survey on Drug Use and Health 72 ).”

PhDs: the tortuous truth [41]

6000 phd student survey by nature.

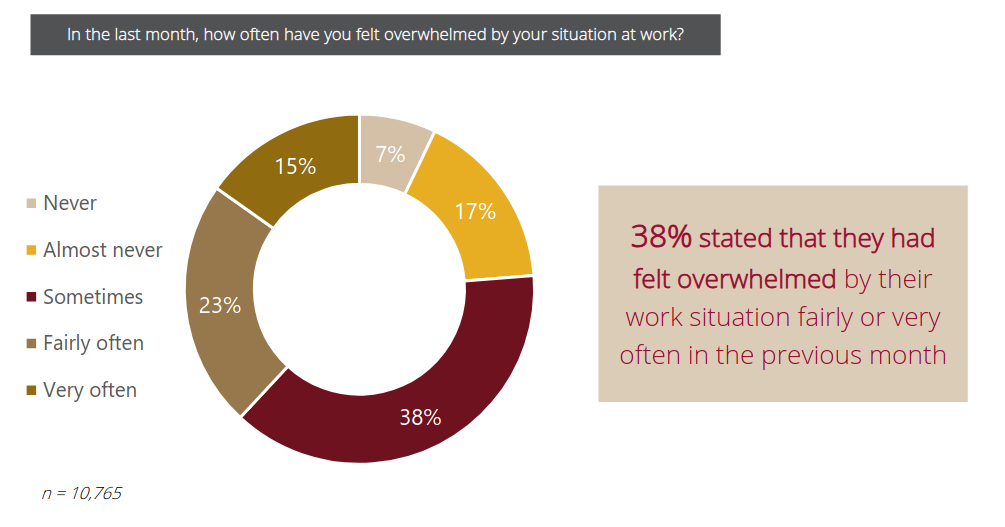

Joy and stress triggers: a global survey on mental health among researchers [42]

survey on 13k researchers over 160 countries

“65% of respondents indicated they were under tremendous pressure to publish papers, secure grants, and complete projects.”

“38% stated that they had felt overwhelmed by their work situation fairly or very often in the previous month”

La gestion du stress chez les doctorants : la surconsommation de certains produits qui pourraient nuire à leur santé [43]

Survey on 438 PhD students:

- “Les résultats indiquent des corrélations significatives entre le niveau de stress perçu, le sentiment d’avoir développé une addiction depuis l’entrée en doctorat et l’année d’inscription en doctorat”

- “Les doctorantEs un niveau moyen de stress perçu plus élevé que chez les doctorant”

- “Les doctorants interrogés, disent avoir augmenté leur consommation de café, de sucreries (bonbons/chocolat), de vitamines, d’alcool et de tabac depuis leur entrée en doctorat dans une proportion qui varie de 51,05 % pour le café à 17,48 % pour le tabac. L’augmentation de la consommation des autres produits (boissons stimulantes, antidépresseurs, somnifères et drogues) est plus faible et n’atteint pas 10 %” (pour les antidépresseurs, 3,5% en consommé avant, et 7,51% en consomme maintenant)

Looking forward

Value of diversity

Diversity leads to better science? Gender-Heterogeneous Working Groups Produce Higher Quality Science [44]

At a ecology and environmental sciences institute, publications by mixed-gender teams are more cited: “While women continue to be underrepresented as working group participants, peer-reviewed publications with gender-heterogeneous authorship teams received 34% more citations than publications produced by gender-uniform authorship teams”

Keywords: diversity, publication citations, better science

Gender-diverse teams produce more novel and higher-impact [45]

In medical sciences, science by mixed-gender teams is better (though underrepresetend, significantly more novel and impactfull):

“We study mixed-gender research teams, examining 6.6 million papers published across the medical sciences since 2000 and establishing several core findings. First, the fraction of publications by mixed-gender teams has grown rapidly, yet mixed-gender teams continue to be underrepresented compared to the expectations of a null model. Second, despite their underrepresentation, the publications of mixed- gender teams are substantially more novel and impactful than t/he publications of same- gender teams of equivalent size.”

Collaborating with people like me: Ethnic coauthorship within the United States [46]

Study over “2.5 million scientific papers written by US-based authors from 1985 to 2008”.

“diversity in inputs by author ethnicity, location, and references leads to greater contributions to science as measured by impact factors and citations.”

The Diversity-Innovation Paradox in Science [47]

Diverse scholars are more innovative, but their work is taken up by others less than it should be

“Prior work finds a diversity paradox: Diversity breeds innovation, yet underrepresented groups that diversify organizations have less successful careers within them. Does the diversity paradox hold for scientists as well? We study this by utilizing a near-complete population of ∼1.2 million US doctoral recipients from 1977 to 2015 and following their careers into publishing and faculty positions.”

“Our analyses show that underrepresented groups produce higher rates of scientific novelty. However, their novel contributions are devalued and discounted: For example, novel contributions by gender and racial minorities are taken up by other scholars at lower rates than novel contributions by gender and racial majorities, and equally impactful contributions of gender and racial minorities are less likely to result in successful scientific careers than for majority groups. These results suggest there may be unwarranted reproduction of stratification in academic careers that discounts diversity’s role in innovation and partly explains the underrepresentation of some groups in academia.”

Improve Hiring

Productivity, prominence, and the effects of academic environment [48]

“we apply a matched-pairs experimental design to career and productivity trajectories of 2,453 early-career faculty at all 205 PhD-granting computer science departments in the United States and Canada, who together account for over 200,000 publications and 7.4 million citations.”

“Our results show that the prestige of faculty’s current work environment, not their training environment, drives their future scientific productivity, while current and past locations drive prominence. Furthermore, the characteristics of a work environment are more predictive of faculty productivity and impact than mechanisms representing preferential selection or retention of more-productive scholars by more-prestigious departments. These results identify an environmental mechanism for cumulative advantage, in which an individual’s past successes are “locked in” via placement into a more prestigious environment, which directly facilitates future success. The scientific productivity of early-career faculty is thus driven by where they work, rather than where they trained for their doctorate, indicating a limited role for doctoral prestige in predicting scientific contributions.”

Minimizing the Influence of Gender Bias on the Faculty Search Process [49]

Workshops on diversity/bias training are somewhat efficient (study at University of Wisconsin-Madison): “In departments where women are underrepresented, workshop participation is associated with a significant increase in the odds of making a job offer to a woman candidate, and with a non-significant increase in the odds of hiring a woman.”

An evidence-based faculty recruitment workshop influences departmental hiring practice perceptions among university faculty [50]

Study over 1188 faculty:

“Faculty had more favorable attitudes toward equitable search strategies if they had attended a workshop or if they were in a department where more of their colleagues had. Workshop attendance also increased intentions to act on two of three recommendations measured. Practical implications: The present studies demonstrate that an evidence-based recruitment workshop can lead faculty to adopt more favorable attitudes toward strategies that promote equitable hiring.” “Balanced applicant pools lead to more equitable outcomes”

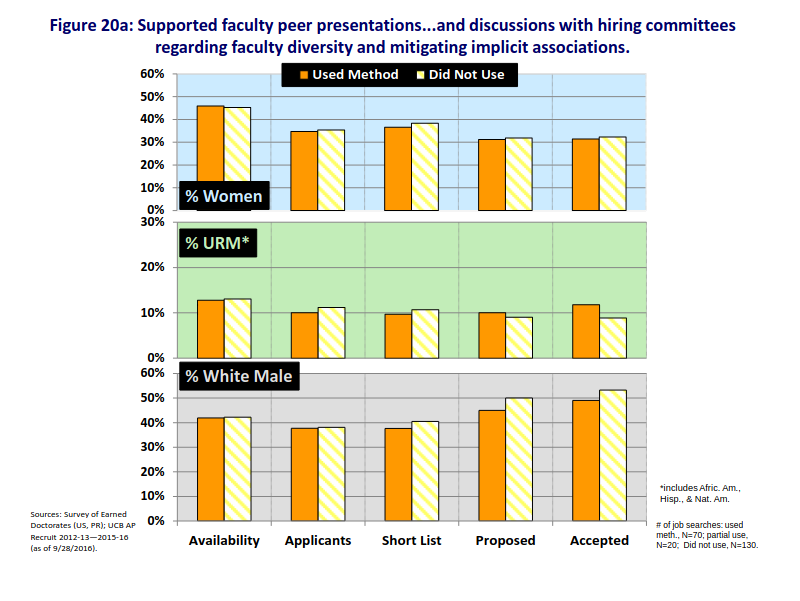

Searching for a Diverse Faculty: What Really Works. [51]

Use data from UC Berkley hirings to study efficiency of approachs w.r.t. diversity hiring: “the 220 searches for which we received survey data represented 94 per- cent of the 29,832 applicants for Berkeley positions from academic years 2012–13 through 2015–1”

Most promising approaches:

- shaping job description “Of all the practices we studied, linking job descriptions to issues of gender, race, or ethnicity had the most impressive positive association with greater diversity.”, “It is not always easy for departments to think outside of traditional disciplinary structures, but our data strongly suggest that this is an effort well worth making when departments want to be sure they are attracting the broadest pools of strong applicants.”

- setting departemental priorities ” some departments also explicitly prioritized hiring faculty who will be able to make strong contributions to the departmental goals for advancing diversity, equity, and inclusion. ”

- mixed committees composition (but put in place teaching hour diminution for women!), “Compared with search committees that did not have at least 40 percent women, those that did were more likely to have higher percentages of both women and URMs under consideration at each search stage” <!> not true in general, see two other papers on the subject here

- targetted outreach “Our research also confirmed the promise of several kinds of targeted outreach that encourage applications from a small number of unusually strong candidates who also would advance the department’s diversity and equity goals”

Some approaches without support: “Our data did not provide support for using three search practices that often are recommended or mandated: reviewing comparative data, taking steps to counter implicit bias, and requiring applicants to provide evidence of their commitment to diversity.”

Does the Gender Composition of Scientific Committees Matter? [52]

“We analyze how a larger presence of female evaluators affects committee decision-making using information on 100,000 applications to associate and full professorships in Italy and Spain. These applications were assessed by 8,000 randomly selected evaluators. A larger number of women in evaluation committees does not increase either the quantity or the quality of female candidates who qualify. Information from individual voting reports suggests that female evaluators are not significantly more favorable toward female candidates. At the same time, male evaluators become less favorable toward female candidates as soon as a female evaluator joins the committee.”

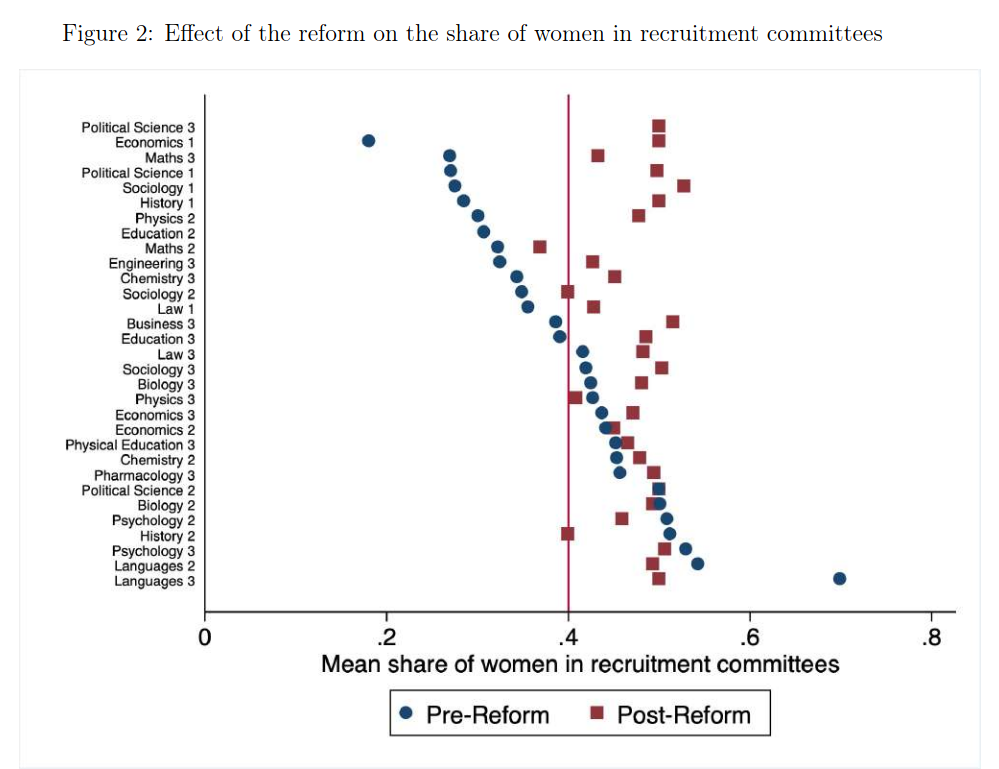

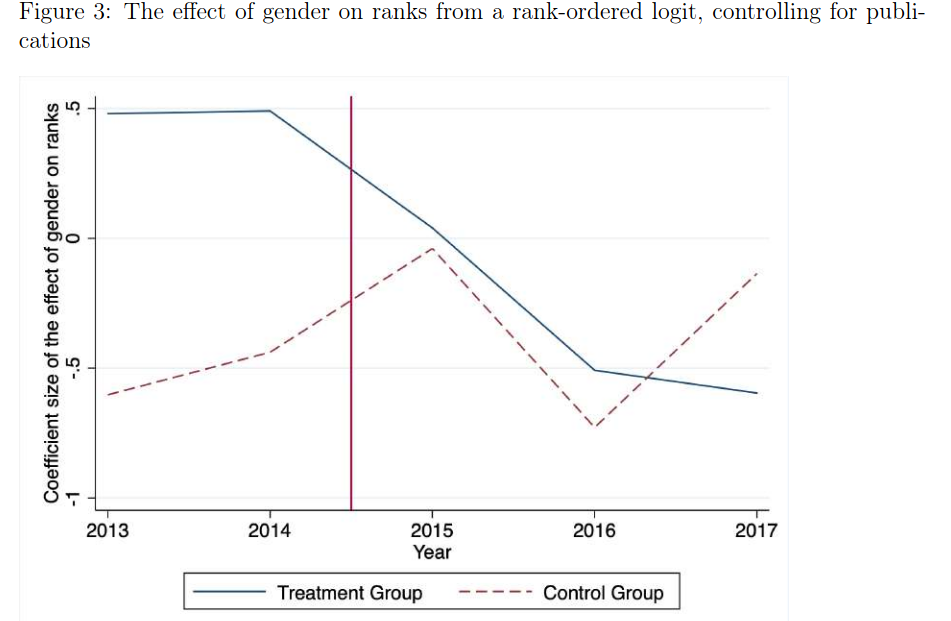

Gender Quotas in Hiring Committees: A Boon or a Bane for Women? [53]

Since French law of 2015, 40% gender quotas in hiring committees.

“Contrary to the objectives of the law, I show that the reform backfired and significantly lowered women’s probability of being hired. Because the negative effect of the reform is concentrated in committees headed by men, this result seems driven by the reaction of men to the reform. I find little evidence that the reform affects supply-side characteristics, such as the likelihood of women applying. The results suggest that the underrepresentation of women is unlikely to be solved by simply increasing the share of women in hiring committees or interview panels.”

The reform did indeed change committees compositions:

But the final ranking of women candidates was negatively impacted, when using as a control group displicines which already had parity vs ones without:

The achievement of gender parity in a large astrophysics research centre [54]

Between 2017 and 2022, the Astro3d center reached parity, from 38% to 50%.

Recruitement measures:

- clear goals in terms of diversity

- diversifiction of team leaders

- 2 day trainging on diversity for everybody, every year.

- minimal quota of 50% of women in postdoc hiring committees

- minimal quota of 50% of women on final postdoc listings

There is a cascading effect (+ leader women -> + postdoc women -> + PhD women),

It is important to recruit AND keep people, **women stay more in women lead teams”.es femmes

Inclusivity Mesures:

- “implicit bias training, members also took cultural, LGBTQIA+, and Indigenous awareness training in subsequent annual retreats, and held monthly seminars on diversity and inclusion”

- “The center’s code of conduct clearly established actions against sexism, insults, microaggressions, and behaviors that excluded other members, and the center had multiple ways of filing misconduct complaints.”

Increasing diversity in STEM academia: a scoping review of intervention evaluations [55]

Lack of none US based data: ” First, over 80% of the articles in this review were based in the US. While this does not mean that interventions are not conducted elsewhere, it does suggest that the current evidence base is predominantly shaped by a particular national context. ”

Need to go beyond gender: “the low numbers of evaluated interventions targeting areas of diversity beyond gender and racial/ethnic minorities is concerning as it may signal low priorit”

Most actions go for individual responsibility: “Moreover, our findings point to the popularity of support-based and diversity training interventions with a disproportionate focus on early career in comparison to, for example, policy changes or interventions that address retention or equity beyond the initial phases of the ‘pipeline’. As will be discussed further below, this pattern appears to speak to an ‘individual responsibility’ approach that prioritises changing the individual over changing the system that disadvantages them”

“Third, the interventions we looked at overwhelmingly reflected ‘master’s tools’, that is they were implemented or endorsed by the institutional contexts that perpetuate the inequalities that are addressed (Morimoto and Zajicek 2014). This is perhaps unsurprising as we were focussing on (largely) top-down intervention rather than grassroots action, but it does raise the question of the extent to which sustainable change is possible.”

Can mentoring help female assistant professors in economics? An evaluation by randomized trial [56]

CeMENT is a single-sex mentoring workshop to support women in research careers. “The program was designed as a randomized controlled trial. This study evaluates differences between the treatment and control groups in career outcomes. Results indicate that relative to women in the control group, treated women are more likely to stay in academia and more likely to have received tenure in an institution ranked in the top 30 or 50 in economics in the world”

Details on the workshop: “The CSWEP CeMENT workshop provides mentoring for women and nonbinary faculty in tenure-track positions at economics departments and similar institutions across North America. Participants are grouped with mentors based on research interests to discuss research projects and career goals. The program also features sessions on publishing, teaching, tenure preparation, grant writing, networking, and work/life balance.”

Reducing discrimination against job seekers with and without employment gaps [57]

“Past research shows that decision-makers discriminate against applicants with career breaks. Career breaks are common due to caring responsibilities, especially for working mothers, thereby leaving job seekers with employment gaps on their résumés.”

“Rewriting a résumé so that previously held jobs are listed with the number of years worked (instead of employment dates) increases callbacks from real employers compared to résumés without employment gaps by approximately 8%, and with employment gaps by 15%.”

Les inégalités de genre dans les carrières académiques : quels diagnostics pour quelles actions ? [58]

“Par ailleurs, une adhésion forte à l’idéal méritocratique – c’est-à-dire à la croyance en un système de promotion et de rétribution basé sur le seul mérite individuel – inter- vient également comme une source potentielle de résistance à l’encontre des mesures égalitaire”

Three different point of view: - “Un registre individuel : quand les institutions académiques s’interrogent sur ce qui « fait défaut » aux femmes”, lead to mentoring, networking - “Un registre sociétal : des institutions académiques confrontées « malgré elles » aux effets des régimes de genre extra-académiques”, help child care, part time dispositives - “Un registre organisationnel : les institutions académiques comme productrices d’inégalités”, fight gender harassment, inclusivity. fight against stereotypes, quotas

Institutions care about image: “Nous avons constaté que les responsables institutionnel·es sont surtout préoccupé·es par l’impact potentiel des mesures de promotion de l’égalité sur l’image de l’institution”

Do Rubrics Live up to Their Promise? Examining How Rubrics Mitigate Bias in Faculty Hiring [59]

Study at Berkley, for over 220 faculty searches.

“This study used a multiple case study methodology to explore how five faculty search committees used rubrics in candidate evaluation, and the extent to which using a rubric seemed to perpetuate or mitigate bias in committee decision-making. Results showed that the use of rubrics can improve searches by clarifying criteria, encouraging criteria use in evaluation, calibrating the application of criteria to evidence, and in some cases, bringing diversity, equity, and inclu- sion work (DEI) into consideration. However, search committees also created and implemented rubrics in ways that seem to perpetuate bias, undermine effectiveness, and potentially contribute to the hiring of fewer minoritized candidates”

“even with a rubric, we witnessed discrimination against international candidates of color, entrenching inequities into evaluation through overreliance on grantsmanship, and a lack of rubrics in later stages that promoted the use of biased personality judgments”

Lack of impact of bias training:

How to improve gender equality in the workplace [60]

” To improve gender equality, we need to debias systems, not people.”

Mixed evidence for diversity statements, diverse selection panel, diversity training, uncousious bias training. Promising things: CV with experiences instead of dates. Use structured interviews for recruitment and promotions,Use skill-based assessment tasks in recruitment, set internal targets for gender representation and equality

Stereotypes and bias (in and beyond academia)

Women are underrepresented in fields where success is believed to require brilliance [61]

“brillance”-focused field lead to less women in them. “The field-specific ability beliefs (FAB) hypothesis aims to provide such an account, proposing that women are likely to be underrepresented in fields thought to require raw intellectual talent—a sort of talent that women are stereotyped to possess less of than men”

“If the practitioners of fields with gender gaps made a concerted effort to highlight the role of sustained, long-term effort in achievement, the gender gaps in these fields may correspondingly be diminished.”

An Emphasis on Brilliance Fosters Masculinity-Contest Culture [62]

“Women are underrepresented in fields in which success is believed to require brilliance, but the reasons for this pattern are poorly understood. We investigated perceptions of a “masculinity-contest culture,” an organizational environment of ruthless competition, as a key mechanism whereby a perceived emphasis on brilliance discourages female participation. Across three preregistered correlational and experimental studies involving adult lay participants online (N = 870) and academics from more than 30 disciplines (N = 1,347), we found a positive association between the perception that a field or an organization values brilliance and the perception that this field or organization is characterized by a masculinity-contest culture. This association was particularly strong among women. In turn, perceiving a masculinity-contest culture predicted lower interest and sense of belonging as well as stronger impostor feelings. Experimentally reducing the perception of a masculinity-contest culture eliminated gender gaps in interest and belonging in a brilliance-oriented organization, suggesting possible avenues for intervention.”

The Development of Children’s Gender Stereotypes About STEM and Verbal Abilities: A Preregistered Meta-Analytic Review of 98 Studies [63]

“This quantitative review of nearly 100 studies shows that, by age 6, children already think that boys are better than girls at computer science and engineering. With age, girls increasingly believe in male superiority in these technical fields—a stereotype that could potentially limit girls’ future aspirations. In contrast, children hold far more gender-neutral beliefs about math ability. Children also think that girls are much better in verbal domains like reading and writing, which could contribute to boys’ underachievement in those domains.”

“Several recent studies have found “brilliance” stereotypes about exceptional intelligence favoring male targets among both child and adult participants in multiple cultures (Bian et al., 2017; Jaxon et al., 2019; Okanda et al., 2022; Shu et al., 2022; Storage et al., 2020; S. Zhao et al., 2022). ”

(Bian et al, 2017 also shows that this impact the activities choosed by children )

“Young children are eager to find, remember, and construct positive information about their gender, driven by in-group gender bias as early as ages 3–5 (Dunham et al., 2016; Halim et al., 2017; Kurtz-Costes, Defreitas, et al., 2011).”

How Preschoolers Associate Power with Gender in Male-Female Interactions: A Cross-Cultural Investigation [64]

In France, Lebannon and Norway, for 4-6 y-o children, children assign the boy role to a dominant gender neutral character. (not so much for 3 y-o)

Looking Deathworthy: Perceived Stereotypicality of Black Defendants Predicts Capital-Sentencing Outcomes [65]

The more somebody “looks like a black person” in front of a jury, the likelier they are to get death penalty.

Against the star culture in math/CS

Stigler law (contributions missatribution) and Matthew effet (cumulative advantage) -> (both themselves missatributions…)

Missattributed research: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_examples_of_Stigler%27s_law

- “Bellman–Ford algorithm for computing the shortest-length path, proposed by Alfonso Shimbel, who presented the algorithm in 1954, but named after Richard Bellman and Lester Ford Jr., who published equivalent forms in 1956 and 1958.”

- “Cantor set, discovered in 1874 by Henry John Stephen Smith and introduced by German mathematician Georg Cantor 1883.”

- “Chernoff bound, a bound on the tail distribution of sums of independent random variables, named for Herman Chernoff but due to Herman Rubin.[20]”

- “Currying, a technique for transforming an n-arity function to a chain of functions. Named after Haskell Curry who had attributed its earlier discovery to Moses Schönfinkel, though the principle can be traced back to work in 1893 by Gottlob Frege.”

- “De Morgan’s laws of logic, transformation rules of propositional logic. Named after 19th-century British mathematician Augustus De Morgan, but already known to medieval philosophers such as Jean Buridan.”

- “The Floyd–Warshall algorithm for finding shortest paths in a weighted graph is named after Robert Floyd and Stephen Warshall who independently published papers about it in 1962. However, Bernard Roy had previously published an equivalent algorithm in 1959.”

- “Gauss’s theorem: first proved by Ostrogradsky in 1831.”

- “Gaussian elimination: was already in well-known textbooks such as Thomas Simpson’s when Gauss in 1809 remarked that he used”common elimination.””

- “Gröbner basis: the theory was developed by Bruno Buchberger, who named them after his advisor, Wolfgang Gröbner.”

- “Moore’s law” -> was a comon notion at the time

- “Russell’s paradox is a paradox in set theory that Bertrand Russell discovered and published in 1901. However, Ernst Zermelo had independently discovered the paradox in 1899.”

- “The Von Neumann architecture of computer hardware is misattributed to John von Neumann because he wrote a preliminary report called”First Draft of a Report on the EDVAC” that did not include the names of the inventors: John Mauchly and J. Presper Eckert”

Missconducts:

- Cantor stole proofs from Dedekin and published them as is own. (https://www.quantamagazine.org/the-man-who-stole-infinity-20260225/)

Just some brain breaking illusions

If some people need to be convinced that our brains lie to us, no matter how strong and rational we believe ourselves to be, this section should help. Of course, bias and stereotypes are more complex than the things below, yet, in many situation with incomplete information and where we are giving our best guess, how can we trust such powerful effects are not at play? (such examples can also be a fun way to engage the audience in a otherwise difficult presentation on the difficult topics discussed here)

Change Blindness

Sometimes, we can’t see something changing right in front of our eyes. Can you see what’s changing between the two blinking pictures?

If you give up, you can click here for the solution

Face recognition

Is their anything wrong with those two pictures of Einstein? By looking closely, you might see some small differences.

Now, flip your screen over and look again. Berk. (or click here)

Bistable optical illusions

A classic, where we either see the dancer going left or right.

Less known is the extended version, where two variants with depth inversion have been added, and looking only at the left or right dancer then changes the rotation direction of the middle one.

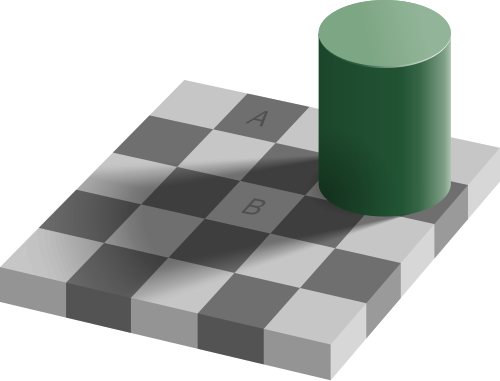

Checker shadow illusion

You will see in the picture below square A and B with clearly distinct colors:

Yet, they are not!

Hidden object

Can you find the hidden object in this picture?

If you give up, click here to see the solution.

Bibliography in Progress

⚙ WIP/TODO

More detailled reading on the notions of power/competition specifically in academia.

⚙ WIP/TODO

Do biblio on how much of the “success” and “merit” is inherited from advisor