Welcome to the home of the not in our labs project, trying to fight back against harassment, discrimination and unwell-being in academia.

The scientific consensus is that we need a global cultural change in academia to address those issues: such a thing can only come from us, the people in academia. This page offers several ressources on how we can do better.

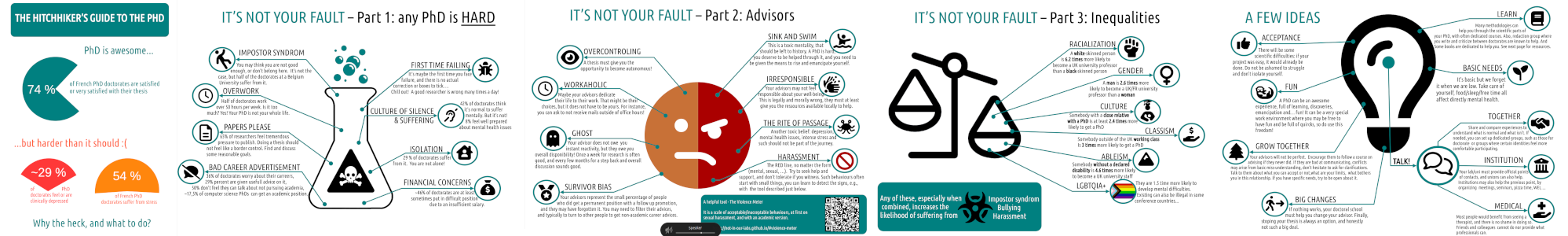

A Hitchiker’s guide to the PhD

The Hitchiker’s guide to the PhD is a small booklet meant to be given to anybody discovering research, during internships, PhDs, or even latter. It summarizes quickly a few key facts, and should make people more prepared for research, and notably learn to discern what is normal, and what is not.

- If you are a PhD student, read it!

- If you are an advisor, read it!

- And otherwise, read it!

This endeavour is essential, as 24% of international doctorates meet the symptoms to be classified as clinically depressed [1], but less than a third (30,1%) of French PhD students consider to be well-informed on all those issues [2], so, it is time to change this!

For a ready to print and fold version, as well the detail of all the sources of the booklet, see here. The booklet can also be used as A3 posters, it makes for a nice office decoration!

A slideshow presentation, for researchers by researchers

To make progress on those issues, we need to be frequently exposed to the subject. As part of the not in our labs project, a presentation has been designed, dubbed “Discriminations, Harassment and Unwell-being in Academia - Understand, React and Prevent”, which is meant to be integrated whithin the usual scientific team/department/lab seminars. It is indeed a scientific talk, meant to be given by researchers and for researchers, and its content is essential to enable us to in fact do good research.

If you are managing such a scientific seminar, you can contact me (charlie.jacomme@inria.fr) and we can try to schedule such a talk (and if you are not managing such a seminar, you can still plant the seed and give my contact). It’s abstract, slides, and highly detailed outline are available here.

Additional ressources

Violence Meter

The violence meter is a prevention tool to spread awareness and help recognize unhealthy and dangerous behaviours in relationships. After an in-depth study, Giorgia Magni made a version dedicated to academia. The original ressoure and its description is in French here.

Find the violence meter in english here, and a more detailed description for each item here. For editable versions, see here and here.

A library of ressources

Paper and reports: all the ressources and references used either for the slideshow presentation or the hitchiker’s guide booklet are listed here, with small comments and main results extracted.

Videos: a compiled list of video presentations on the topic, with a few highlighted recommendations, is available here.

Some home-made statics on gender gap in French Computer Science

Some statistics dedicated to the field of computer science were produced and detailed here, to be able to give a clear connection point for the booklet and the presentation. It is a side additional project, which also highlights some of the issues talked everywhere here.

External ressources

A few french associations on the subject:

And a few final ressources:

- Le violentomètre du doctorat

- Guide de l’autodéfense universitaire

- Fiches d’infos techniques sur le doctorat

Homepage logo

Logo is a modified public domain picture from Linnaea Mallette.